On July 1, 2023, the Wet Toekomst Pensioenen (WTP) was introduced, a new law aimed at comprehensively reforming the pension funds market in the Netherlands. While it provides for a transition period that can extend until January 2028, the market is already in motion, with many funds announcing plans to implement the reform as early as 2026.

Why is it important? Because this quiet but far-reaching reform of the €1.5 trillion Dutch pension system, shifting from a defined benefit (DB) model to a defined contribution (DC) model, is set to trigger a profound structural shift across Europe’s government bond markets and interest rate swap curves. Under the new DC framework, Dutch pension funds will move away from guaranteeing retirees a fixed payout and instead set up individual accounts whose final value depends on contributions and investment performance, rather than a fixed promise (as in a DB model). At first glance, this might seem like a technical adjustment. But the consequences are likely to ripple across euro-denominated government debt, swap spreads, and curve dynamics.

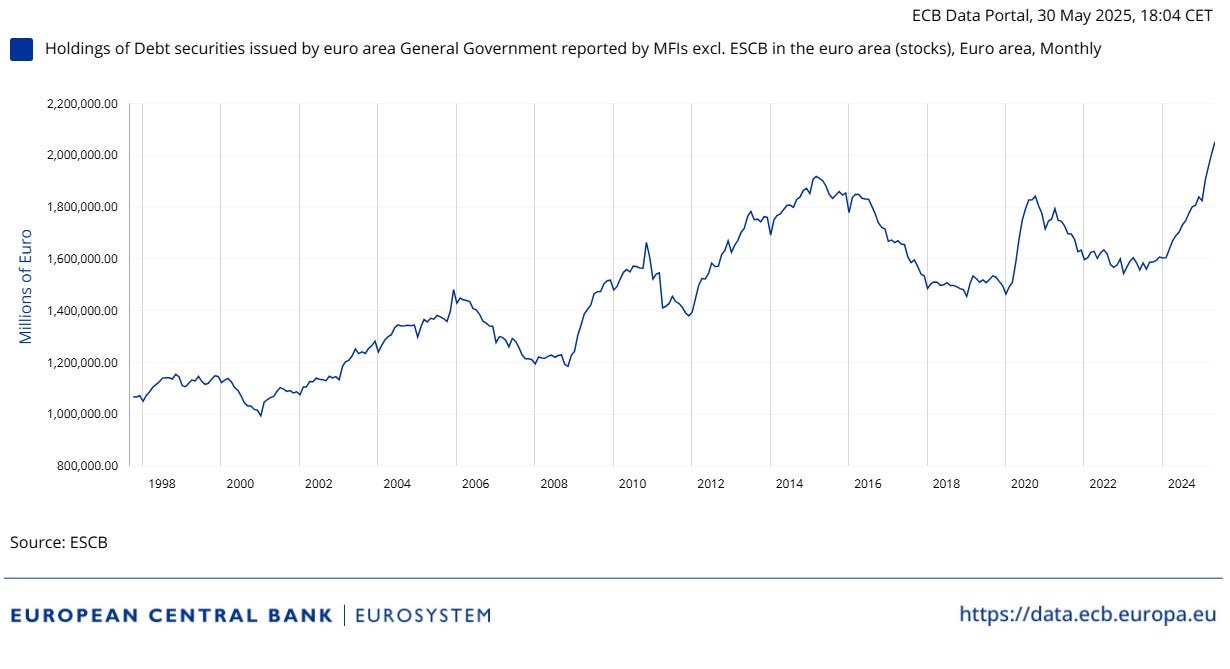

Before addressing the issue of Dutch pension funds, it’s important to note that the timing of the reform (although it will be finalized by January 2028) is ill-suited. It comes at a moment when demand for government bonds is already declining, and the ECB is undergoing a process of quantitative tightening or QT (meaning it is reducing its balance sheet by letting securities mature without reinvesting, thereby withdrawing liquidity from the market). Alongside this QT, and most likely during and after the Dutch pension reform, European banks will once again be “called upon” to act as dealers. The problem is that these banks already have very high exposure to government bonds, and Basel IV regulations will further complicate matters (as discussed here).

Secondly, we’re also seeing a trend among Asian investors (for instance, Japanese investors) to significantly reduce their holdings of Eurozone government bonds, especially after Germany’s decision to pass a constitutional amendment modifying the “debt brake”. If we also factor in that the UK gilts market is undergoing the same kind of “transformation” (namely, a gradual decoupling of pension funds from sovereign debt markets), it becomes clear there is a real risk of a broader, cross-regional loss of demand for government bonds. The reasons are varied: from concerns about repayment capacity, to banking regulations, to the regulatory transformation of NBFIs, and so on.

In this light, the Dutch pension reform, even if it seems local and without major systemic implications, could in fact reshape a significant part of Europe’s financial architecture.

First of all, pension liabilities are long-term promises. Under the traditional DB system, Dutch pension funds guarantee fixed payments to retirees often decades into the future. Because these payments depend heavily on long-term interest rates, the value of those future obligations changes as rates move. This is where duration comes in, as it measures how sensitive pension liabilities are to interest rate changes. This point is important because a Dutch pension fund is primarily evaluated by its coverage ratio (known in Dutch as the “dekkingsgraad”), which precisely measures the ratio between the fund’s assets and its discounted liabilities. This ratio must consistently remain above 110%; if it falls below that level, the pension fund risks losing its ability to index benefits. For those unfamiliar with Dutch: “vermogen” refers to the fund’s assets, while “VPV” denotes its future liabilities (as in the figure below).

Source: Witteveenbos

As such, the longer the duration, the more sensitive the liabilities are. So if interest rates fall1, the present value of these obligations increases, meaning the fund owes more in today’s terms. To manage this “risk”, pension funds hedge their exposure to falling rates by holding assets that rise in value when rates decline, a strategy known as duration matching. They do this mainly by building large portfolios of long-dated government bonds, often with maturities stretching 20 to 50 years, and by entering into receive-fixed interest rate swaps at the ultra-long end of the curve. These swaps involve agreeing to receive fixed interest payments and pay floating rates over long horizons (typically 20 to 50 years). Essentially, swaps act like synthetic bonds, allowing funds to lock in steady income and protect against rate drops, matching their long-term pension promises and lock in future liabilities, even for the youngest members whose retirements are decades away.

But as the system transitions to DC, the direct obligation to guarantee specific payouts vanishes. Employers will now only be responsible for contributions, and future benefits will hinge on market performance rather than predetermined promises. This fundamentally reduces the funds’ need to own ultra-long duration assets. Instead, capital will be reallocated towards higher-yielding assets such as equities and credit, which offer better expected returns but carry more risk.

That is why Rabobank estimates that nearly €127 billion of long-dated sovereign debt will be sold by Dutch pension funds over the transition, primarily affecting German, French, and Dutch government bonds. Why these in particular? Because in the 20-year and 30-year segments, these bonds and euro interest rate swaps are widely used for hedging, but also because of their relative lower yield). This represents a significant structural shift in demand at precisely the time when Europe’s sovereigns, from Germany’s ambitious €1 trillion investment plans to broader Eurozone defense and energy projects, are issuing record levels of debt.

The impact on yields is already visible. The yield on Germany’s 30-year Bund has risen from below zero during the pandemic to over 3%, levels reminiscent of the Eurozone debt crisis.

Meanwhile, the yield curve has steepened sharply, with the spread between France’s 30-year and two-year yields widening by over 2 percentage points. To say nothing of effects that few could have foreseen just a few years ago: Italian bonds (relatively riskier, although heavily used in European repo markets) have now experienced a yield curve inversion relative to French bonds, effectively becoming “cheaper”, first time since 2005. A surprising move, especially given the traditional safe-haven status of the French public debt. And the structural pressure is likely to intensify further, as more Dutch pension funds, including giants like ABP and PFZW, complete their transitions starting in 2026.

Source: Bloomberg

Returning to our main issue, beyond the cash bond market, the most acute effects may appear in the swap market, where Dutch pension funds have been dominant receivers at the long end. Historically, as part of their activity, these funds played a stabilizing role: their demand for long-dated swaps helped anchor the 30- and 50-year points, compressing term premia and flattening the curve. As these positions unwind, banks and other market participants expect bear steepening, with the long end moving higher relative to the 10- or 20-year sectors. Estimates foresee a steepening of the 10s30s swap curve by 10 to 30 basis points over the medium term (meaning demand for ultra-long receive-fixed swaps declines and the 30-year swap rates, for example, could rise more than 10-year rates).

Source: ColumbiaThreadNeedle

In more detail, current projections suggest that until around 2028 there will still be sustained demand for interest rate swaps. However, as noted above, this demand is expected to decline significantly once the pension reform takes full effect. How would this affect the cost of interest rate swaps? Last month, I discussed that these swaps in Europe had effectively reached negative levels (although the market may have shifted since then). Yet the Dutch pension reform could alter the trajectory of these prices. For instance, Dutch pension funds are huge relative to the euro fixed income market, with total assets ≈ €1.5–1.7 trillion (depending on market moves). Among these, the largest funds (e.g., ABP, PFZW) each manage hundreds of billions.

Moreover, Dutch pension funds hedge falling discount rates by receiving fixed in very long euro interest rate swaps (mostly 20–50 years). Their total DV01, the amount they gain or lose if rates move by 1 basis point, is about €900–1,100 million. In other words, if long rates drop by 1bp, they lose around €1 billion. This makes them some of the biggest structural buyers of fixed rates at an European level, especially since the daily turnover in the euro 30y swap market is only a few € billion. To put it simply, a typical 30y swap has around €1 million DV01 per €100 million notional. So €900–1,100 million DV01 means pension funds effectively hedge around €90–110 billion notional (think of it as a 1% percent).

After the reform, it’s estimated they might cut receive-fixed positions by €300–500 million DV01, roughly 30–50% of their current exposure. That equals about €30–50 billion less in long swap demand. Given the euro 30y swap market’s annual turnover is about €700–800 billion, this drop is around 4–7% of yearly flow. As such, based on these numbers, such a decline in structural demand can push 30y swap rates up by about 5–15bps over time (somehow in line with the steepening aforementioned). Of course, these are just rough estimates, and the actual market impact could differ once the reform takes effect, but it shows why Dutch pensions matter so much for the very long end of the euro swap curve.

As such, part of the repositioning is mechanical. Ahead of the switch, funds are incentivized to protect their funding ratios by adding hedges, buying long-dated interest rate swaps or bonds. But once the transition date passes, the incentive flips: funds rush to shed these hedges to align portfolios with new, shorter liability profiles. This creates a dilemma: hedge too early, and you risk front-running yourself; hedge too late, and you might be the last to exit in a crowded trade. The figure below illustrates just how crucial the 30-year swap rate is in relation to the “dekkingsgraad” (coverage ratio):

Source: ING

Adding complexity is the recent Dutch government decision to allow funds up to a year of "post-sorting", a window to readjust hedges after the transition without immediately triggering large market moves. Yet this very announcement has fueled speculation, as hedge funds (as counterparties of pension funds) position to anticipate the flows, potentially amplifying volatility rather than smoothing it.

In essence, the Dutch pension reform illustrates how regulatory and demographic changes can have market-wide consequences. A system built around guaranteeing predictable income over decades is giving way to one driven by market returns, freeing capital to chase higher yields, but at the price of withdrawing structural support for the longest-dated euro government bonds and swaps.

For policymakers, the challenge is clear: Europe’s sovereigns need buyers for a flood of new debt, but a key pillar of demand is structurally weakening. For traders and investors, the pension transition is a structural force that, combined with fiscal expansion and ECB policy, is likely to reshape curves and spreads in the euro rates market for years to come.

Pension funds want to hedge against falling rates by holding assets (like long government bonds) that increase in value when rates fall. Rising rates are less of a concern because they actually reduce the size of the pension fund’s liabilities, which is a good thing for the fund’s funding status.