Today's post will differ slightly from previous ones, as it focuses on a structural shift within the financial system - one that, perhaps unsurprisingly, has largely escaped public attention. Given the implications, however, it warrants far greater scrutiny. This post is part of a broader series that will examine how the modern banking system operates, with a particular focus on emerging interconnections that may pose systemic risks.

Over the past decade, private credit has emerged as one of the fastest-growing segments of global finance. Once a niche corner of alternative asset management, the sector has now surpassed $1.6 trillion in assets under management globally, with the US market alone accounting for approximately 60% of that figure. This rapid expansion has occurred alongside a notable shift in credit intermediation - from regulated banks toward non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs), including business development companies (BDCs), private equity-backed direct lenders, and credit funds.

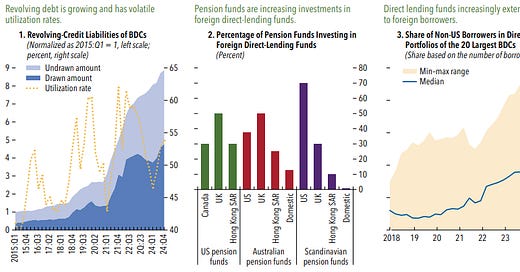

Source: International Monetary Fund

Contrary to the common narrative of decentralization and de-risking, recent developments suggest that private credit is becoming deeply intertwined with the regulated banking system. This entanglement raises new questions about financial stability, regulatory arbitrage, and the effectiveness of post-crisis reforms.

Private credit assets under management (AUM) has more than tripled since 2015. In 2023, the sector saw record capital inflows, and BDCs issued $24 billion in bonds, a new high. The appeal for investors is clear: higher yields than public markets and favorable structural terms, including tighter control over borrowers.

However, the credit quality underlying this growth is deteriorating. According to the IMF’s 2025 Global Financial Stability Report, over 40% of borrowers in the direct lending universe now operate with negative free cash flow. Many are reliant on payment-in-kind (PIK) interest, “amend-and-extend” restructuring clauses, and flexible covenants that mask underlying distress, as argued in the aforementioned report.

Credit spreads in the private space have not adequately compensated for this deterioration. While yields on middle-market loans remain above 10%, this pricing has not fully captured rising default risk or liquidity premia, particularly for loans originated outside the top 10 direct lenders. Furthermore, exit markets (via refinancing or M&A) remain weak, increasing mark-to-model risk across portfolios.

But private credit is not a self-funded ecosystem. Direct lenders are heavily reliant on bank-provided liquidity via subscription credit lines or asset-based lending (ABL) facilities. What are these? For instance, a subscription credit line (or subscription credit facility) is a short-term loan provided to a private equity or private credit fund, secured by the capital commitments of its investors. Instead of immediately calling investor capital for each new investment, the fund can draw on the credit line to finance deals quickly, then repay the loan once it makes a capital call to its investors. At the same time, ABL is a type of financing where a company borrows money secured by its assets - such as accounts receivable, inventory, equipment, real estate, whatever - rather than relying primarily on cash flow.

Source: International Monetary Fund

Interestingly, many of the largest transactions occur across jurisdictions with limited regulatory coordination - for example, Japanese banks' exposure to US BDC, often structured through entities registered in the Cayman Islands. This aligns with one of my research papers, in which I argue that the Cayman Islands should not be seen merely as an offshore financial center, but as a jurisdiction exercising infrastructural power vis-à-vis the United States. A significant portion of the US financial system is functionally embedded within this Caribbean jurisdiction.

According to Barclays estimates, global banks have extended over $500 billion (!) in credit facilities to private credit funds, equating to roughly 25–30% of global private credit AUM.

This exposure is not evenly distributed. US and Japanese banks are especially active in the space. Japanese megabanks such as Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation (SMBC) and MUFG are key providers of funding to US BDCs. In Europe, banks such as BNP Paribas, Société Générale, and Deutsche Bank offer structured leverage to private credit funds through total return swaps and synthetic facilities.

The implication is clear: far from being an isolated asset class, private credit is partially underwritten by bank liquidity. In the event of credit deterioration, the impact will be transmitted upstream to the regulated banking system, blurring (once again, remember GFC of 2007-9?) the boundary between shadow and core.

As a result, banks are increasingly offloading the credit risk associated with these exposures using Synthetic Risk Transfers (SRTs). These structures - akin to credit default swaps but customized and privately negotiated - allow banks to retain the asset on balance sheet while shedding the credit risk to third-party investors, often insurance companies, pension funds, or credit funds. In the US, they are usually fully funded, meaning investors provide the protection upfront in cash. This is typically done through a credit-linked note (CLN) - a security that pays returns in exchange for bearing credit risk. The CLN may be issued directly by the bank or through a special purpose entity (SPE) (in Cayman Islands). More about SRTs here.

The use of SRTs has grown rapidly in the past few years. For example, even for European banks, the European Banking Authority reported close €160 billion in SRT volumes for 2023. But returning to US and Japan, a landmark example occurred just weeks ago when SMBC executed a $3 billion SRT referencing credit lines to US BDCs - effectively blending bank financing with synthetic risk distribution to private markets.

SRTs provide capital relief under Basel rules by reducing risk-weighted assets (RWAs), allowing banks to extend more credit without raising new equity. However, they do not eliminate the exposure, they repackage and redistribute it to institutional investors that may have limited visibility into the underlying collateral. In the event of a systemic event, correlation risk could render these protections ineffective, as occurred during the 2007–2008 synthetic collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) unwind.

It is actually the recent positioning by macro hedge funds that suggests rising skepticism toward the sustainability of private credit valuations. As of Q1 2025, hedge funds have built over $1.8 billion in short positions across listed direct lenders such as Ares Capital, Blue Owl, and Apollo BDC. According to S3 Partners, these shorts have returned $1.7 billion YTD in paper profits.

The key thesis behind these positions is that funding costs are rising faster than loan yields, compressing net interest margins (NIMs), while defaults and markdowns are poised to accelerate as amendments and PIK accruals become unsustainable.

However, if these lenders incur significant losses, the impact will ultimately spill over into the balance sheets of traditional banks. This is precisely why the growing nexus between private credit and the banking sector deserves closer scrutiny.

In a nutshell, the promise of private credit was that it would decentralize risk and provide a flexible alternative to bank lending. In reality, it has become a critical node in a rebundled, increasingly complex financial system. Banks remain at the core of this structure - not as disintermediated actors, but as liquidity providers, risk transformers, and residual bearers of market fragility.

totally agree. I worked in Leveraged Finance through 08-09 crisis until 2014, when the European credit funds began to blossom pushing the banks out of this market thanks to very lax documentation provisions and immense leverage on offer. Now facing the downturn, the foundation begins to shake and portfolios deteriorate, which is probably the main drive we see that European banks extend loans to NBFIs like crazy in an attempt to avoid spillover. But we all know it will eventually happen anyways :)