NAV Lending: Blessing or Curse?

Let me start with the conclusion. Net Asset Value (NAV) lending is here to stay! Of course, this opens a Pandora’s box, with both positive and negative implications. There are many benefits, for example, NAV lending has become a strategic, even crucial, topic precisely because of the liquidity pressures rippling through private equity and private credit (something I discussed in Monday’s post). Originally a niche tool for mature funds seeking flexible capital in the mid- to late stages of a fund’s life, NAV lending has now become a rapidly expanding market. But what it actually does? In a nutshell, it bridges the liquidity gap caused by slower exits and constrained fundraising, allowing funds to continue operations and deploy capital even in a (let’s say) challenging macroeconomic environment. Unlike early-stage subscription lines, NAV facilities rely on the value of a fund’s portfolio rather than the uncalled commitments of investors, creating a very different risk and collateral profile.

But what on Earth is NAV lending? At its core, NAV lending is fund-level credit where a fund borrows against the net asset value of its existing portfolio. In this context, NAV is essentially the sum of a fund’s assets minus its liabilities, usually expressed per unit of the fund. It reflects the current valuation of the fund’s holdings. For example, if a private equity fund owns several portfolio companies and those holdings are valued at $500 million, and the fund has $50 million in outstanding debt, the NAV is $450 million. Lenders use this NAV as the collateral base to determine how much they are willing to lend. Based on that, lenders apply a haircut or a LTV (loan-to-value) ratio to account for valuation risk, liquidity, or diversification. For example, if a fund has a $450 million NAV and the lender applies a 30% LTV, the fund could borrow up to $135 million.

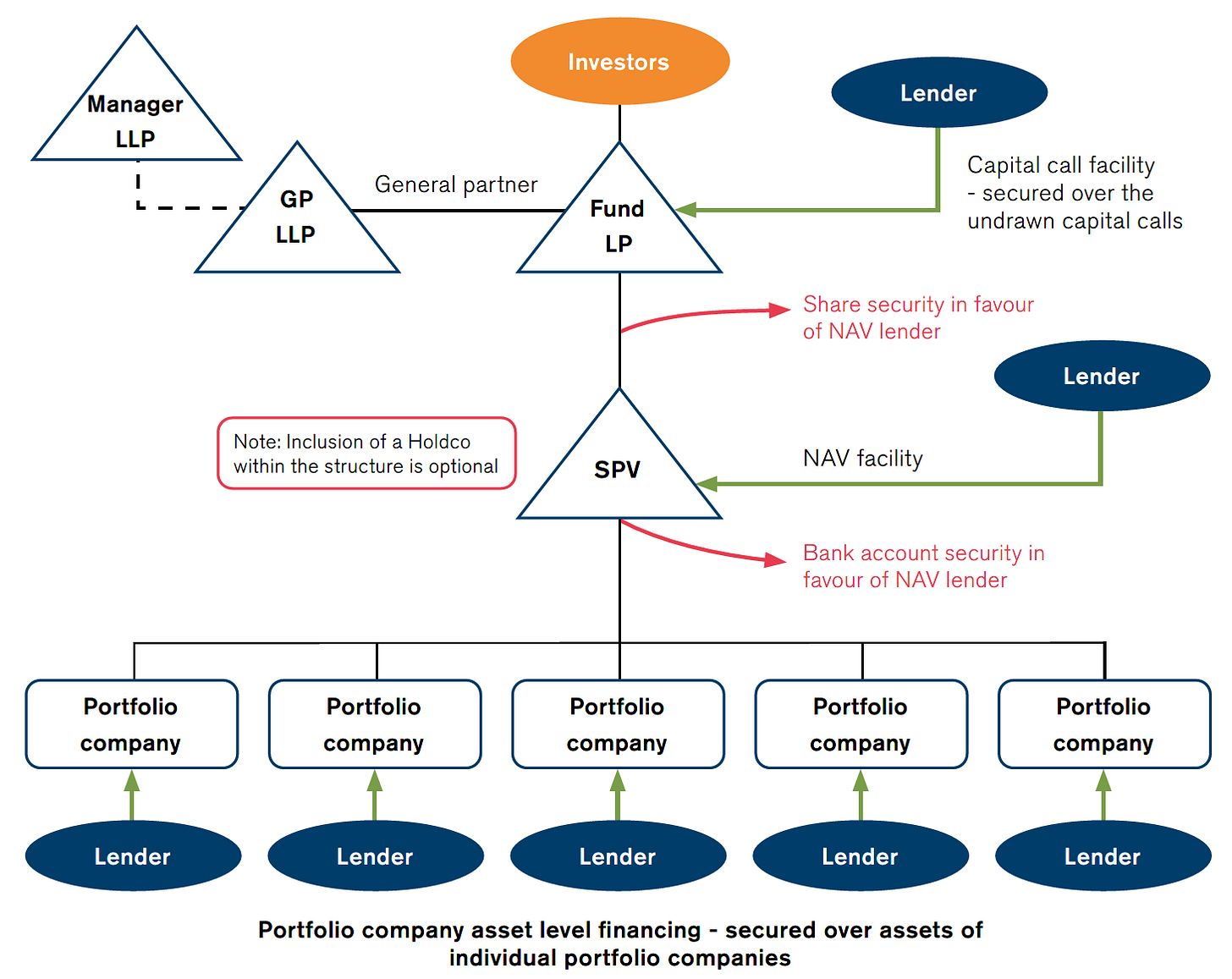

In plain English, for private equity, private credit, and secondary funds, this means using the collective value of portfolio companies, loans, or other investments as collateral. Of course, NAV lending isn’t the only financing tool, as we already know. This is part of a broader ‘package’ alongside subscription lines and asset-backed lending. But what does each of these actually mean? Subscription lines, sometimes referred to as capital call facilities or sub-lines, are loans secured by unfunded commitments from limited partners (LPs). Subscription lines are typically deployed early in a fund’s lifecycle to bridge the timing between capital calls and investments (more about this here). Asset-backed lending, by contrast, is often deal-specific, secured by individual assets or special purpose vehicles (SPVs), and usually targets the underlying company rather than the fund itself. NAV lending thus occupies a middle ground: it is fund-wide, flexible, and designed for use once the portfolio is substantially invested, rather than at the inception of the fund.

And so, NAV lending has evolved in structure and sophistication. Unlike subscription lines, which are generally revolving and predictable, NAV facilities often require *complex* valuation processes and can be structured as either term loans or revolving lines. The facility may be secured over the entirety of a fund’s portfolio or a select subset of investments. Loans are usually non-recourse to LPs, meaning that lenders have recourse only to the fund’s assets, not the individual investors, though covenants and security over SPVs are common. Otherwise put, when a private fund takes out a NAV loan, the lender can only claim repayment from the assets held within the fund itself, not from the personal wealth of the fund’s LPs, meaning if the fund defaults, LPs are not personally on the hook for the debt.

The rise of NAV lending reflects a convergence of market forces. Bank retrenchment following the 2023 disruptions at SVB and Credit Suisse reduced the availability of balance-sheet-intensive lending. Regulatory pressures under Basel III and subsequent Federal Reserve updates increased capital costs for banks providing fund finance, prompting many to diminish this activity.

Source: Brookfield Oak Tree

And so, private credit funds stepped into this vacuum, offering greater flexibility, tailored terms, and higher yields (albeit at higher risk). Meanwhile, private equity fund managers faced liquidity mismatches driven by slower exits and declining public market valuations (as discussed in Monday’s post). Exits in 2023 fell sharply, nearly 40% year-over-year, leaving capital tied up in portfolio companies while the need for follow-on investments or distributions to LPs persisted. NAV loans provide another mechanism for bridging these gaps without forcing asset sales at depressed prices, allowing managers to preserve value and continue strategic portfolio deployment. The figure below shows an example of a private equity fund with a NAV financing.

Source: Private Capital Solutions

NAV lending also offers clear benefits to General Partners (GPs). It provides liquidity without the need for distressed asset sales, extending the fund’s investment horizon and smoothing distributions to LPs. In the case of private equity, NAV loans allow GPs to reach multiple goals. For instance, NAV loans support portfolio companies, fund add-on acquisitions, refinance expensive asset-level debt, and/or deliver distributions without diluting equity stakes (more about this here). For private credit funds, NAV lending functions as fund-level leverage, enabling them to recycle capital but also to amplify returns to investors. For LPs, the benefits are more indirect but (still) significant: delayed capital calls reduce cash drag, which helps in preserving the portfolio momentum.

The risks inherent in NAV lending, however, are both structural and subtle. One primary concern is hidden leverage. Fund-level borrowing is often consolidated into a single line item and may not be fully disclosed in standard reporting metrics. When combined with sub-lines and asset-level debt, the overall leverage stack can be opaque. During a market downturn, this opacity can exacerbate liquidity stress, particularly if multiple facilities must be repaid simultaneously or collateral values decline rapidly (this is was the topic of this post on private credit). Valuation ambiguity compounds the problem. NAVs are manager-assessed and typically updated quarterly or semiannually, leaving room for lagged or inflated asset values. Lending against stale NAVs exposes both lenders and LPs to the risk of overextension. And so, in a stress scenario, collateral values may deteriorate faster than the fund can adjust, triggering defaults or forced sales.

Another concern is portfolio cross-contamination (higher-order exposures anyone?). NAV loans are often secured against multiple assets, so a default in one portfolio company can affect the recovery of others. Lenders have the right to step into the fund and access proceeds from different portfolio assets, potentially undermining otherwise healthy investments. This dynamic can reduce recoveries for LPs and introduce correlation risk across supposedly diversified holdings. Covenant breaches present an additional source of risk. Many NAV facilities include covenants tied to NAV thresholds or portfolio performance metrics1. Volatility-induced breaches can trigger technical defaults, forcing funds to liquidate assets in unfavorable conditions to satisfy lenders.

The controversy surrounding NAV lending intensifies when used to fund distributions to LPs, a practice sometimes referred to as “leverage on leverage”. In these cases, the NAV facility sits senior to LPs in the fund’s capital structure, meaning that as assets are realized, lenders are repaid first, and distributions to investors are effectively advanced from borrowed money. While this can boost reported IRRs, it raises alignment issues and introduces risk that may not be immediately apparent in fund metrics. Fortunately, surveys from Rede Partners and industry data indicate that the majority of NAV facilities (approximately 89%) are used for “money-in” purposes such as growth capital or add-on acquisitions, while only a minority, around 11%, have been used for “money-out” distributions2. LPs generally support money-in uses but are more cautious regarding distributions funded by NAV loans, reflecting awareness of the inherent leverage risk.

The NAV lending market has grown rapidly, with estimates indicating approximately $150 billion in outstanding loans as of 2023, up roughly 30% annually over the prior four years. Major private credit players, such as Pemberton Asset Management, have launched new NAV funds, often anchored by large institutional investors like sovereign wealth funds. Despite its growth, NAV lending remains opaque, and market data is limited. This opacity is both a risk and an opportunity: sophisticated investors can access high-yield, fund-level leverage if they conduct careful due diligence, but mispricing or misunderstanding the underlying assets can result in losses.

In evaluating NAV facilities, LPs and co-investors should consider several dimensions: the intended use of proceeds, the composition and quality of the collateral pool, covenant terms, and the lender base. Stress testing NAV assumptions, understanding valuation methodologies, and assessing liquidity management strategies are all essential to avoid systemic or idiosyncratic shocks. NAV lending is not inherently dangerous, but the combination of leverage, portfolio-level collateral, and discretion in use makes it a double-edged tool.

In conclusion, NAV lending has emerged as a cornerstone of contemporary fund finance, providing liquidity and flexibility to funds navigating slower exits or fundraising constraints. It is materially different from subscription lines and asset-backed loans in collateral type, timing, and risk profile. While it offers substantial benefits for GPs and, indirectly, for LPs, NAV lending introduces new types of risks (structural, valuation, governance and so on) that require careful monitoring. For investors and fund managers alike, the task is to balance the operational advantages of NAV facilities with the vigilance needed to manage risk, ensuring that fund-level leverage remains a tool for value creation rather than a source of unintended fragility. Hard to believe, but it’s Friday, and I want to wrap up the week on a positive note.

Covenants are legally binding promises or conditions that the fund (the borrower) agrees to follow as part of the loan agreement. They are designed to protect the lender by ensuring the fund maintains certain financial or operational standards.

In Money-in, the borrowed capital is reinvested into the fund’s portfolio. Examples include financing add-on acquisitions, supporting portfolio companies, or refinancing existing debt. Essentially, the loan increases the fund’s investment capacity and potential returns. For money-out, the borrowed capital is used to pay distributions to investors (LPs) or cover fees, rather than being reinvested. This can boost reported IRRs but doesn’t expand the fund’s assets, and it carries higher risk because it leverages the fund without generating new economic value.

Great article! I run a NAV lender (nodem.com).

Exceptional breakdown of NAV lending and its structural complexities. The distinction you draw between subscription lines, asset-backed lending, and NAV facilities is crisp and clarifies a market that's grown to $150B but remains remarkbly opaque. What's particularly relevant about this analysis is how firms like Ares Management are positioned on multiple sides of these transactions. Ares provides NAV financing through their private credit platform while also managing funds that use NAV facilities themselves, which creates intresting dynamics around both origination discipline and how they structure their own leverage. The point about hidden leverage and portfolio cross-contamination is critical because when you stack sub-lines, NAV facilities, and asset-level debt, the real leverage can be 2-3x what appears in headline metrics. Ares has been relatvely transparent about their approach to fund-level leverage, but the industry-wide opacity you describe is a systemic concern. The 89% money-in vs 11% money-out statistic from Rede Partners is reassuring, but the temptation to use NAV loans for IRR engineering is real, especially when exits remain constrained. Your warning about valuation ambiguity is spot on, quarterly or semiannual marks create dangerous lags in stress scenarios. Really thorough work here.