In March 2025, the Bank for International Settlements released a report with potentially significant implications, though it attracted little attention, for various reasons.

The report showed that in the first half of 2024 (with data covering up to June 2024), large internationally active banks reported a modest but clear rise in Basel III risk-based capital ratios, signaling - at least on the surface - a strengthening of financial buffers. According to the latest Basel III monitoring exercise, the Tier 1 minimum required capital (MRC) for Group 1 banks rose by 1.9%, up from 1.3% at the end of 2023. Yet this apparent fortification of balance sheets comes with a familiar warning: while capital levels are higher, the underlying risk profile of banks may not have improved and may even be worsening in more opaque ways.

This discussion must also be placed in the context of other indicators, which suggest a relatively stable overall picture.. The leverage ratio and Net Stable Funding Ratio (NSFR) remained flat at 124%, and although the Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) slipped slightly to 136%, only three banks fell below the 100% minimum threshold. But the rising prominence of risk-weighted capital measures, and the relative inertia of simpler indicators like the leverage ratio, raise concerns about the effectiveness of risk-based metrics in signaling real financial stability.

The core issue is the built-in manipulability of risk-weighted frameworks. Unlike the leverage ratio - which simply measures capital against total assets regardless of risk weights - risk-based capital ratios offer banks room to “optimize” their asset mix to maximize compliance with minimum thresholds without actually increasing equity funding. This isn’t new. Prior to the 2007–08 crisis, the Recourse Rule, which introduced Basel II-style risk weights for securitized tranches, encouraged banks to load up on highly-rated but ultimately fragile structured products like collateralized debt obligations (CDOs), collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) and so on. These were, in practice, the very instruments that enabled the rapid spread of the financial crisis. The reduction in capital requirements for AAA-rated tranches gave banks a regulatory incentive to tilt their portfolios toward assets that ultimately proved toxic.

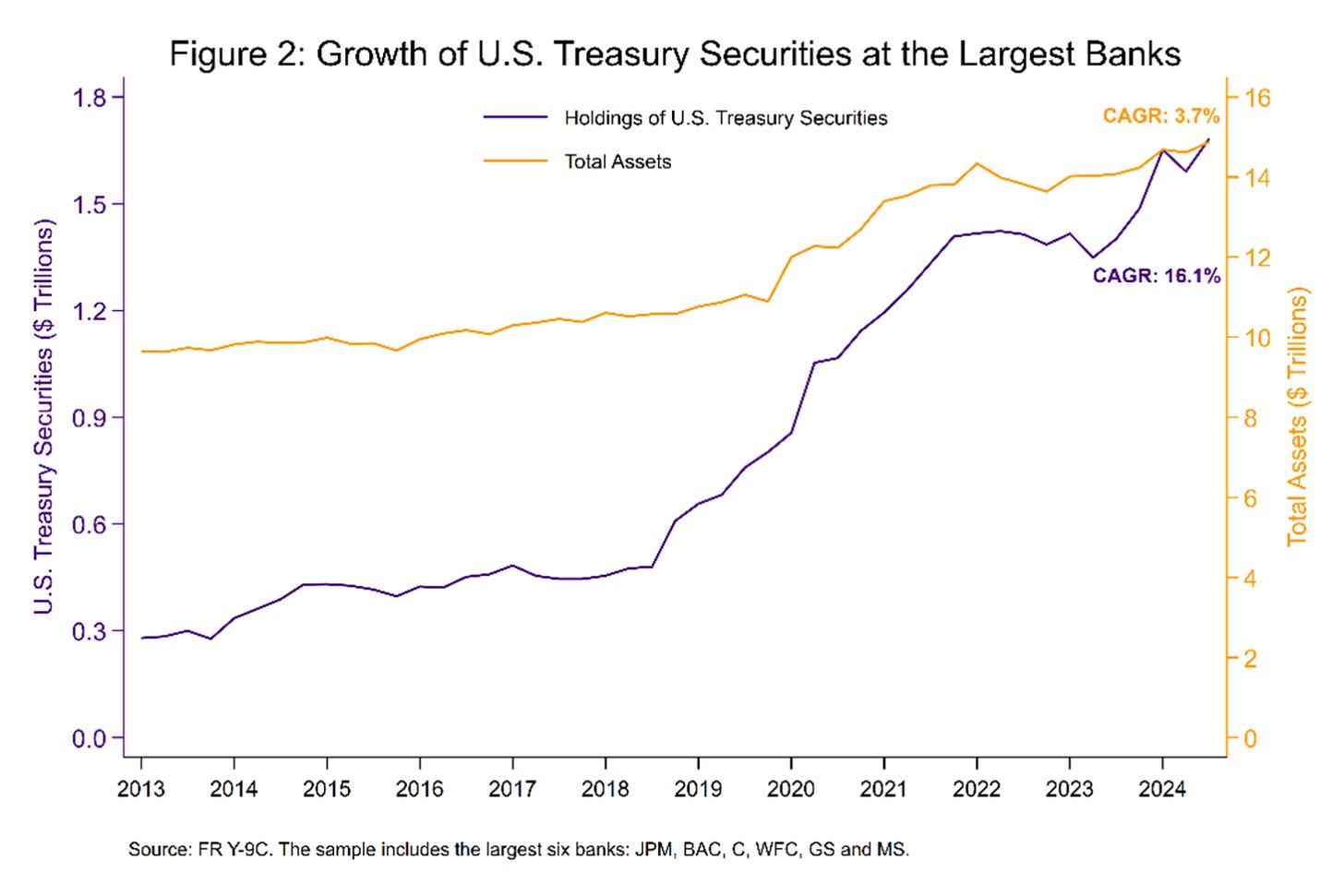

Fast-forward to 2024-2025, and we may be witnessing a similar dynamic (but this time, without necessarily referring to an increase in exposure to complex financial instruments). Higher capital requirements under Basel III may prompt (or prompted) banks - particularly those designated as “advanced approaches” institutions - to hold more sovereign debt or central bank reserves, assets which carry low or zero risk weights. A study from the early Basel III implementation period in the US (2013–2014) showed that large banks responded to new capital standards not by raising equity or expanding lending, but by sharply increasing their holdings of reserves and then Treasuries. This substitution effect meant that capital ratios improved, but lending to the real economy stagnated. It is the same today.

There is also the question of capital efficiency and profitability. Empirical studies using data from over 1,900 banks across 39 OECD countries reveal that while higher quality capital (e.g., common equity) improves efficiency and profitability, risk-based capital ratios fail to reduce actual risk. Moreover, they may diminish the efficiency and profitability of highly liquid banks, which already comply with LCR and NSFR requirements. In other words, additional capital does not always equate to added resilience and may, in fact, distort incentives and reduce the allocative function of banks.

Here lies a deeper conceptual tension: equity capital regulation is designed to absorb unexpected losses, acting as a final buffer against system-wide shocks. Risk-based capital, by contrast, aims to transform unexpected losses into expected ones through the modeling of asset risk, thus creating a regulatory illusion of control. But the risk weights used in this transformation are, themselves, subject to political economy, assumptions, and model errors. Instead of strengthening resilience, this architecture risks replacing blunt uncertainty with the false precision of spreadsheets. A crisis, by definition, is when the unexpected overwhelms the expected (Silicon Valley Bank crisis, anyone?).

Compounding this is the opacity of internal risk models. Banks using internal ratings-based (IRB) approaches have historically demonstrated significant latitude in how they assign risk weights. Regulatory arbitrage remains a key feature of how large banks manage their capital ratios. As with the pre-crisis era, these institutions can adjust their portfolio composition to improve capital metrics without meaningfully de-risking their balance sheets.

All these observations help further clarify why banks significantly increased their holdings of US Treasuries during a period when, paradoxically, intermediation in these markets was subject to certain constraints. These limitations contributed to the emergence of an alternative market structure, one that plays a central role in the trading of these instruments and, by extension, their derivatives, particularly Treasury futures (I’ve discussed this topic in more detail here, here, or here).

Source: Bank Policy Institute

Thus, this serves as yet another confirmation that post-GFC regulations - notably Basel III, the G-SIB surcharge, and stress testing - have significantly weakened incentives for new lending. These measures have led banks to cede a substantial share of corporate lending to non-bank financial institutions (more on that here), while simultaneously increasing their holdings of high-quality liquid assets such as US Treasuries. However, this shift has also resulted in reduced participation in certain repo transactions, primarily due to higher regulatory costs.

This trend aligns with findings from the Bank Policy Institute, which noted that:

“Since larger banks face higher capital requirements for loans than smaller banks, they have shifted their portfolio toward liquid assets such as Treasury securities and away from loans”

Ultimately, while the phased implementation of Basel III continues, its reliance on risk-based metrics may have introduced a paradox: banks appear stronger on paper, but more fragile in reality. They seem more capable, on paper, of supporting the real economy, yet in practice, they are less able to do so due to legal constraints and rising costs. Without deeper reforms that re-anchor capital requirements to simpler, more transparent measures, the next crisis may originate from the shadows of a well-capitalized system.

amazing 👍