Today we continue along the lines introduced yesterday. In that post, I argued that the growing role of hedge funds in the US Treasury market reflects a deep structural shift in financial intermediation. As traditional bank-affiliated primary dealers become increasingly constrained by post-crisis regulations and balance sheet limitations, hedge funds have emerged as key actors in absorbing the growing supply of government debt and facilitating liquidity through arbitrage trades - most notably, the Treasury cash-futures basis trade and the swap spread trade. However, this market-based substitution introduces a set of fragilities that policymakers are only beginning to fully grasp.

The cash-futures basis trade exploits a pricing gap between Treasury securities and Treasury futures contracts. How does it work? Hedge funds purchase the underlying Treasury bonds - often financed via short-term repurchase agreements (repos). Why a repo? Because hedge funds usually operate with lean balance sheets, so they don’t fund these purchases with their own capital. Instead, they borrow the money through repo transactions, using the Treasury securities as collateral. Simultaneously, they sell short an equivalent futures contract. This futures contract is typically purchased by a bond manager or mutual fund who wants exposure to Treasury interest rates but doesn’t want to buy the bonds outright, since that would tie up too much cash. In this context, a Treasury futures contract offers similar exposure to holding the bonds but requires significantly less upfront capital.

In theory, the basis trade is low risk, as it arbitrages mispricings that tend to converge at contract settlement. Yet, the low margin per unit of capital deployed makes the strategy highly dependent on leverage. As hedge funds stretch their balance sheets to multiply returns, they become increasingly exposed to liquidity and interest rate volatility.

A closely related arbitrage is the swap spread trade, which involves going long Treasuries and short interest rate swaps, betting on a mean reversion of the spread between the two. Like the basis trade, it is perceived as a relative-value strategy with tight margins and high leverage. However, it is typically conducted over-the-counter (OTC) and often lacks the centralized clearing and margin transparency of exchange-traded futures. The swap spread trade has become an increasingly popular vehicle for expressing views on regulation, fiscal risk, or monetary policy, often amplifying market moves when expectations abruptly shift.

Recent data suggest the magnitude of these leveraged arbitrage trades is substantial. Hedge funds now account for roughly 11% of the US Treasury market, with basis trades estimated at around $1 trillion. To support these trades, hedge fund borrowing in repo markets has surged by $1.5 trillion since late 2022, with the top ten funds accounting for the majority. This form of intermediation is now systemically relevant, not only because of its scale but due to its interconnectedness with broader market functioning. The figure below illustrates both the growing importance of repo transactions for hedge funds but also the increasing volume of bank financing directed toward them.

Source: International Monetary Fund

One important feature of this new regime is the shift from balance sheet intermediation by primary dealers to synthetic leverage through derivatives and repo financing. Macro and relative-value fixed income hedge funds - two of the strategies most exposed to basis and swap spread trades - now exhibit gross notional leverage of 40x and 25x their assets, respectively. These levels far exceed those previously deemed prudent in bank-led intermediation models. While this expansion has facilitated liquidity and price efficiency in Treasury markets under normal conditions, it has simultaneously created a latent source of procyclical instability.

A case in point occurred in the aftermath of the April 2, 2025 tariff announcements. The sudden increase in market volatility led to higher margin requirements on futures contracts and rising repo rates, both of which undermined the profitability of the basis trade. At the same time, the recalibration of rate expectations triggered sharp losses in swap spread trades. Facing deteriorating mark-to-market valuations and tightening liquidity conditions, hedge funds began unwinding both trades en masse. This deleveraging wave amplified selling pressure in Treasury markets, widened bid-ask spreads, and forced additional margin calls - a self-reinforcing dynamic that further destabilized market conditions.

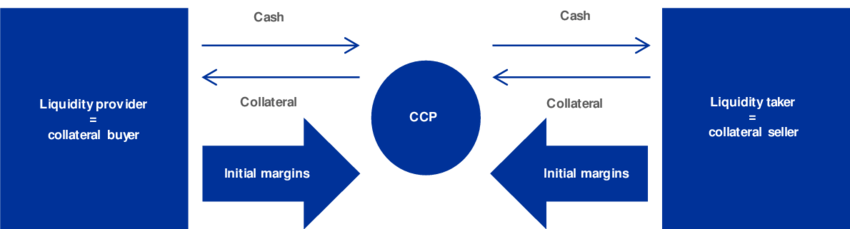

For more clarity, an a cash-futures basis trade, margin calls are applied on the futures leg, which is centrally cleared through a CCP. These calls occur when market volatility or price movements increase the required variation margin, forcing hedge funds to post additional collateral. On the cash leg, where Treasuries are typically financed via repos, there are no formal margin calls, but similar effects occur through changes in repo haircuts or rising repo rates, which tighten funding conditions and can force deleveraging.

Source: ESRB

This episode illustrates a broader concern: while hedge funds have stepped in to fill the liquidity void left by constrained primary dealers, they lack the capacity - or perhaps the incentive - to act countercyclically in moments of stress. Unlike banks, hedge funds are not backstopped by central banks (not yet at least, see below). Their use of leverage is often opaque, and their risk management practices are heterogeneous. As such, the Treasury market has become more vulnerable to sharp and disorderly repricings, particularly when trades that rely on stable funding and narrow spreads are unwound in synchrony.

Moreover, the increasing footprint of hedge funds raises deeper questions about the structural resilience of Treasury markets. The market is now roughly five times the size of primary dealer balance sheets, a significant increase from just 1.5x two decades ago. This mismatch means that traditional dealer intermediation is no longer sufficient to absorb shocks, and that the system now relies more heavily on actors whose behavior is intrinsically more procyclical. In the absence of regulatory oversight comparable to that applied to banks, the potential for systemic deleveraging remains a live risk.

Source: International Monetary Fund

Paradoxically, regulatory solutions such as higher margin requirements or central clearing for repo transactions - intended to reduce systemic leverage - could themselves trigger destabilizing unwindings. The very instruments designed to promote market safety may amplify stress under the wrong conditions, particularly when implemented abruptly or without sufficient backstop mechanisms.

In sum, the rise of hedge funds as quasi-intermediaries in the US Treasury market has helped maintain liquidity and facilitate issuance in an era of fiscal expansion and constrained bank balance sheets. But it has also introduced a new layer of structural vulnerability, one centered on the dynamics of leverage, liquidity, and rapid unwinding.

This is why there are discussions and even calls for the Federal Reserve (naturally, who else?) to become a synthetic lender of last resort. Why? As hedge funds unwind their cash-basis positions, these can typically be absorbed by dealers. However, if the dealers' balance sheets, as we've discussed, are already constrained, this could lead to fire sales of basis positions that can generate a significant dislocation between cash and derivatives prices. This has significant implications for other financial segments as well, as deleveraging occurs, resulting in a widening of the basis between cash Treasuries and derivatives. Potential solutions discussed include increasing dealer capacity by adjusting the supplementary leverage ratio (which would allow dealers to allocate more balance sheet space to the UST market), imposing minimum margin requirements on repo-financed Treasury purchases, and, perhaps most importantly, creating a repo facility by the Fed specifically for hedge funds. However, just like with other Federal Reserve purchasing programs, everything sounds good in theory until you encounter the practical challenges. Simply providing a repo facility to hedge funds cannot prevent or stop a large unwind of basis trades, just as in 2020, the mere exclusion of USTs from leverage ratio calculations for banks and primary dealers didn’t solve the issue. In this regard, it has been argued that the Fed should alter its role relative to this new funding structure. If we witness an unwind of a hedged long-cash Treasuries/short-derivatives position, it has been suggested that the Fed could take the opposite side of this unwind by purchasing USTs and fully hedging this acquisition with an offsetting sale of futures contracts.

As Hyman Minsky famously argued, we are constantly trying to stabilize an inherently unstable economy. This instability stems precisely from the procyclical behavior of most actors operating in the core segments that underpin the global economic system.