In European banking supervision, few topics stir as much quiet but consequential debate as the use of internal models to calculate regulatory capital. For years, large banks across the continent have relied on their own credit and market risk models (of course, subject to supervisory approval) to determine how much capital they must hold against their exposures. This practice reflects one of the central compromises of the Basel II framework: if a bank could demonstrate that its risk management systems were sophisticated enough, it could be trusted to model its own risks more accurately than a one-size-fits-all standardized formula.

That compromise, however, has proven far more fragile in practice than it looked on paper. The financial crisis of 2007–08 exposed weaknesses in the way some internal models captured credit and market risks (both in the US and Europe). Subsequent reviews showed wide variation in model outputs across banks holding similar portfolios. What was meant to be risk-sensitive capital allocation often turned into model arbitrage: the same loan could attract vastly different capital charges depending on how a bank’s model was specified. For regulators, this variability undermined the comparability and credibility of capital ratios (not to say that for markets it eroded trust).

Of course, there is a compelling case for internal models. Banks with large, complex balance sheets argue that standardized approaches fail to reflect the nuances of their portfolios. A model calibrated with granular, bank-specific data can produce capital requirements that are both more risk-sensitive and more efficient. Internal models, at least in theory, align regulatory capital more closely with the actual risk management practices of sophisticated institutions. That can prevent overcapitalization and reward institutions that genuinely manage risk well.

But there is also a darker side. Internal models are not neutral. Most of the time, they are the product of assumptions and methodological choices. A small change in how default probabilities or loss-given-default rates are defined can swing risk-weighted assets (RWAs) by billions of euros. Even without malicious intent, models can be gamed, tweaked, or optimized to deliver capital relief rather than true risk reflection. Supervisors know this, which is why every model must be approved, validated, and subject to ongoing investigation. But the scale of the task is immense, and supervisory resources are finite.

As such, the European Central Bank, through the Single Supervisory Mechanism (SSM), has gradually tightened its oversight of internal models. Its “Targeted Review of Internal Models” (TRIM), concluded in 2021, was an unprecedented effort to harmonize model supervision across the euro area. TRIM revealed significant inconsistencies and forced banks to remediate deficiencies, with the explicit goal of reducing unwarranted variability in RWAs.

More recently (July-August 2025), the ECB updated its Guide to Internal Models to align with the changes introduced under CRR3 (the EU’s implementation of the Basel IV package). The guide now reflects stricter standards on data governance, internal validation, and the use of new techniques such as machine learning (more about this subject here). It also clarifies supervisory expectations for credit risk models, counterparty credit risk, and the treatment of exposures during margin periods. Importantly, the ECB has signaled a shift. Alongside reactive investigations triggered by banks’ own applications, it will step up proactive investigations in areas deemed high-risk or strategically important.

The supervisory message is clear. Banks must simplify their models and revert to standardized approaches for smaller or less material exposures. Indeed, many institutions have already done so: the number of rating systems across significant banks fell by nearly a fifth between 2022 and 2024.

And that’s because supervisory investigations are the hinge point of the entire internal model regime. Every time a bank wants to introduce a new internal model, extend an existing one, or make material changes, the ECB must review and approve it. These investigations are supposed to ensure that the models reflect actual risk and that governance and validation frameworks are sound. In practice, however, the workload is enormous. During the TRIM exercise, the ECB launched hundreds of investigations simultaneously, uncovering deficiencies in almost every significant institution. That campaign required massive supervisory resources and stretched both the ECB and the banks. Even today, the pipeline of model investigations is heavy as banks adapt to CRR3 and the Basel IV output floor. And because of that, many are reverting portfolios back to standardized approaches or applying for new models in specific areas, each of which triggers a new round of supervisory review.

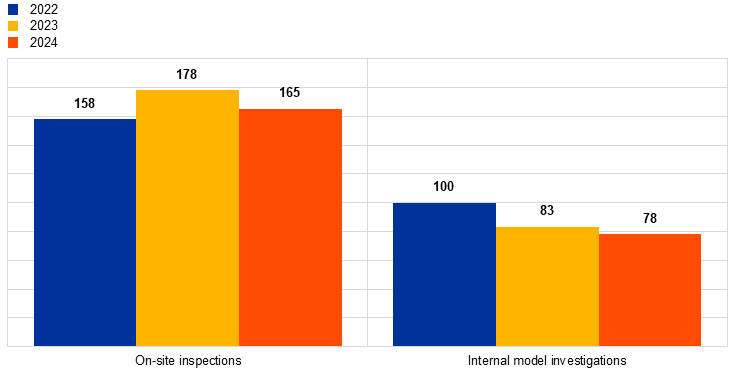

Source: ECB Annual Report on Supervisory Activities

The problem is that the ECB does not have infinite resources. Investigations are time-consuming and require specialized expertise. When dozens of banks submit applications at the same time, bottlenecks are inevitable. This creates two risks: either approvals are delayed for months or even years, leaving banks in regulatory limbo, or investigations are rushed, leaving open the possibility of inconsistencies across institutions. Neither outcome is satisfactory and it raises some questions. I’m not saying the decline in internal model investigations (as can be seen in the figure above) is necessarily because of this, but it does make you wonder…

This bottleneck effect is one reason why the ECB has encouraged banks to simplify their model landscapes. A proliferation of models means not only higher operational costs for banks, but also supervisory overload for the ECB. By pushing institutions to concentrate internal models on truly material portfolios and shift marginal portfolios back to standardized approaches, the ECB is effectively managing its own capacity problem.

But of course, it should be made clear that not all models demand the same resources. Mortgage portfolios or standardized SME exposures, for instance, generate fewer supervisory headaches. By contrast, large corporate loans, sovereign exposures, derivatives, and trading books are far more problematic. These portfolios are not only central to banks’ balance sheets, but also highly sensitive to capital requirements. Any small change in assumptions can move risk-weighted assets (RWAs) by billions.

That’s why the segments most affected by ECB scrutiny have been low-default portfolios, counterparty credit risk models, and trading book models. Low-default portfolios (like sovereigns or large corporates) suffer from a lack of empirical data, forcing banks to rely heavily on internal assumptions (a space where supervisory discretion becomes decisive). Derivatives portfolios pose their own challenge, because counterparty credit risk and credit valuation adjustment (CVA) models depend on highly technical modelling of netting sets or margining assumptions (among others). Trading book models, meanwhile, have come under intense review as the Fundamental Review of the Trading Book (FRTB) demands a complete recalibration of market risk measurement.

This dynamic exposes why relying exclusively on internal models is risky: supervision itself becomes a scarce resource. Even the best-designed regulatory framework falters if the supervisor cannot credibly investigate and approve the sheer volume of model changes. That is precisely why Basel IV pushes toward output floors and greater use of standardized approaches: to reduce the reliance on supervisory resources that are inherently limited, and to make the capital framework less dependent on complex, bank-specific modelling.

Basel IV (also discussed in detail here), finalized in December 2017 and scheduled for phased implementation in the EU under CRR3/CRD6 from 2025 (potentially stretching to 2030, or later, given the frequent delays), represents the Committee’s attempt to redefine the role of internal models. Instead of discarding them entirely, Basel IV boxes them in, placing constraints on where they can be used, how far they can deviate from standardized metrics, and how supervisory approval is obtained.

The most consequential Basel IV reform for internal models is the output floor. By 2030, a bank’s total RWAs as calculated using internal models must be no lower than 72.5% of what they would be under the standardized approach. This simple rule changes everything. In practice, it means that the gains from having sophisticated models are capped. If a bank’s model says its mortgage book requires €80 billion of RWAs, but the standardized approach implies €120 billion, the bank cannot report less than €87 billion (72.5% of €120 billion). This floor limits the variability of outcomes and makes internal models less decisive in driving capital numbers. The impact differs across portfolios. Banks with conservative modeling practices and well-diversified books may find their models still comfortably above the floor. Others (especially those heavily reliant on low historical default rates to drive down PDs) will find themselves constrained.

Another major shift under Basel IV is the selective restriction of model use. Certain asset classes are deemed unsuitable for advanced modeling because of inherent data limitations or observed misuse. In equity exposures, the Advanced IRB (AIRB) approach is eliminated outright. Banks must use either the standardized or a simplified approach. For specialized lending (e.g., project finance, commodities finance), banks may only use the foundation IRB at most. For low-default portfolios (sovereigns, large corporates, banks): PD and LGD parameters are subject to stricter floors and constraints, reducing flexibility.

The third dimension is market risk. Under Basel II and III, banks could use internal models for their trading books, but model approval was relatively permissive. The FRTB, incorporated into Basel IV, tightens this dramatically. FRTB requires banks to meet strict profit & loss attribution (PLA) tests and risk factor eligibility tests in order to use internal models. Many desks are expected to fail these thresholds, forcing banks back onto the standardized approach. Even when models are approved, the capital requirements are more conservative, reducing the benefit relative to standardized calculations.

As a synthesis, the European banking system now sits at a crossroads. Internal models will remain part of the architecture, but they will be more narrowly applied, more tightly supervised, and more constrained by standardized benchmarks. The ECB will continue to refine its guide, intensify its investigations, and push banks toward simplification. The broader goal to restore credibility to regulatory capital by striking a balance between risk sensitivity and comparability. This is important because too much reliance on internal models, and the system drifts into opacity and inconsistency. Too little, and it risks bluntness and inefficiency. Basel IV represents an attempt (perhaps imperfect) to find that balance.

In practice, banks will need to accept that internal models are no longer engines of capital relief, but tools for fine-tuning in strategic areas. Supervisors, for their part, will need to ensure that model investigations do not become bottlenecks that paralyze adaptation. And markets will need to recalibrate their trust in reported capital ratios, understanding that variability is now bounded but not eliminated.

The evolution of internal model supervision in Europe may lack the drama of market crises or monetary policy debates. Yet it touches the very core of how banks measure risk and allocate capital.