The European government bond repo market plays a crucial role in ensuring the smooth functioning of the euro area’s financial system. At its most basic level, it enables the flow of cash and high-quality collateral from those with excess to those in need, facilitating liquidity, supporting monetary policy transmission, and contributing to broader market stability. Of course, this is a simplified account of how repo markets operate; in reality, the system is far more intricate, as explored in one of my co-authored papers. Yet regardless of whether we approach European repo markets from a simplified or highly theoretical perspective, one thing is clear: in recent years, the market has increasingly experienced stress, marked by pricing dislocations, infrastructure fragmentation, the emergence and disappearance of certain asset classes, and more. These developments are now driving a growing debate about the potential merits of mandating central clearing across the European repo market.

As such, at the heart of this conversation is the recognition that the current market structure, while functional, is no longer optimal. Regulatory reforms in the wake of the global financial crisis, the rising prominence of non-bank financial intermediaries (NBFIs), and repeated central bank interventions have altered the operational dynamics of repo markets (for the best or for the worst). These shifts are leading policymakers, infrastructure providers like Eurex, and large market participants to reassess whether the current mix of bilateral and centrally cleared repo trades can ensure long-term systemic stability. In a nutshell, a centrally cleared repo is a repurchase agreement where a central counterparty (CCP) steps between the buyer and seller, becoming the legal counterparty to both sides and managing counterparty risk through margining, netting, and default management mechanisms.

It is precisely these changes in the structure of US repo markets (and the US Treasury market) that have made the Securities and Exchange Commission’s (SEC) 2023 mandate for the central clearing of US Treasury repos a source of renewed urgency in the European debate (we discussed the SEC’s goal here). While the US market was starting from a lower base of central clearing (just 20–30%), the decision marked a clear policy shift: systemic resilience was prioritized over operational convenience. In Europe, where roughly 60% of government bond repo volumes are already centrally cleared, the marginal benefits may appear smaller. But the debate is far from settled.

Why is that? Because Europe’s unique market fragmentation - spanning sovereign issuers, clearing systems, and settlement practices - complicates direct policy transposition from other jurisdictions. Nevertheless, several critical arguments support expanding central clearing.

First, central clearing imposes stricter risk management standards. Haircuts, margining, and collateral eligibility are subject to transparent and prudently calibrated rules. This stands in contrast to the bilateral segment, where up to 70% of trades in both Europe and the US reportedly feature 0% haircuts, effectively enabling hidden leverage, particularly among hedge funds and other NBFIs. During stress periods, this leverage can unwind in procyclical ways, overwhelming bank dealers and amplifying systemic risk.

Second, central clearing enhances netting efficiency and counterparty risk mitigation. By interposing a CCP between buyers and sellers, credit exposures are reduced and more efficient use of balance sheets becomes possible. Importantly, this could free up capacity for bank intermediation, an especially salient point given the tightening regulatory environment and rising reserve demand across the financial system.

Third, central clearing offers a pathway toward better integrating NBFIs into the institutional framework of market stability. However, existing regulatory and accounting standards were not designed with NBFIs as direct CCP participants in mind. Current frameworks prevent funds from re-using cash or collateral to meet CCP margin calls, impose counterparty concentration limits that are misaligned with CCP risk structures, and exclude repos from favorable capital treatment afforded to centrally cleared derivatives. These regulatory mismatches create unnecessary barriers that suppress both market efficiency and resiliency.

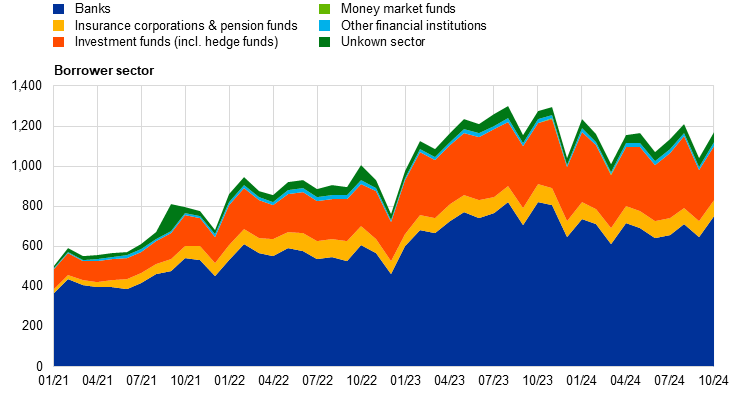

Why are NBFIs so important? Because these entities - including money market funds (MMFs), pension funds, insurance companies, and hedge funds - now account for a substantial and expanding share of trading activity (in government bond markets), particularly in the uncleared segment. While their role is still not comparable to that of European banks, the trend is unmistakably upward.

As such, despite the potential efficiency gains of broader central clearing, the design of existing NBFI regulatory frameworks has failed to anticipate - or enable - wider participation in centrally cleared repo markets. For instance, if Europe is to unlock the full potential of cleared repo markets, some barriers must be dismantled. As Eurex has argued, regulatory frameworks for UCITS and insurance firms should be modernized to allow for pledge and reuse of collateral in bankruptcy-remote structures, aligning them with CCP requirements (received in a reverse repo transaction). Funds are also restricted from reusing cash or collateral received in repo transactions to meet margin requirements at CCPs. This significantly reduces operational efficiency, as they must secure alternative liquidity to fulfill margin calls.

Insurance companies face parallel challenges. Solvency II has only extended favorable capital treatment to centrally cleared derivatives, not repos. Although European regulators have acknowledged this gap, industry trade associations have thus far resisted expanding preferential treatment to include repos, out of concern for operational complexity or unquantified risk. Thus, it was argued that Solvency II should clarify and apply explicitly the preferential risk weights accorded to credit institutions as Clearing Members also to insurance undertakings and pension funds.

Another element is related to MMFs. For example, MMFs, a central clearing pillar in the US, face EU rules that limit counterparty concentration. Since a CCP becomes the sole counterparty in cleared transactions, these concentration limits are hit far more quickly than in bilateral markets with multiple dealer relationships despite the lower credit risk profile of CCPs. Put simply, current regulations impose a 15% counterparty exposure cap for EU money market funds (MMFs) and a 20% cap for UCITS, but neither includes specific rules addressing CCPs. Meanwhile, the AIFMD framework lacks any such counterparty exposure limits altogether. These regulatory approaches fail to account for the fact that a CCP, by design, becomes the counterparty to all trades it clears, meaning it would reach those limits more quickly than other institutions.

In stress scenarios, NBFIs - especially leveraged funds - can become forced sellers, overwhelming dealer intermediation capacity and causing sharp collateral price swings. By centralizing counterparty risk and facilitating multilateral netting, CCPs can improve liquidity, reduce procyclicality, and act as shock absorbers. Importantly, central clearing doesn’t just mitigate risk ex post, it disciplines leverage ex ante by imposing stricter margining and collateral standards.

Let me be clear: I firmly believe that expanding the clearing mandate would bring meaningful benefits. However, such an expansion must be accompanied by a broader set of reforms that address the growing systemic importance of NBFIs. Without this, the effort risks being futile.