As discussed over the past few days (here, here, or here), the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) - and especially its enhanced version (eSLR) - has emerged as a pivotal regulatory constraint on the intermediation capacity of the largest US bank holding companies. Unlike risk-weighted capital ratios, the SLR applies a non-risk-sensitive measure by requiring a minimum capital buffer against total leverage exposure, including low-risk assets such as US Treasuries and Treasury repos. As bank balance sheets have grown, particularly through increased holdings of Treasuries, the SLR has become binding for several systemically important institutions. Currently, three of the six largest US bank holding companies are constrained by the eSLR, limiting their ability to absorb additional Treasury assets without either shedding other assets or raising capital - both of which are costly and capital-inefficient, especially under market stress.

This capital rigidity has had unintended consequences. When the SLR becomes binding, banks and primary dealers are incentivized not to expand their low-risk activities - such as Treasury intermediation or repo market participation - but instead to pull back (and focus on different segments, such as equity margin loans to hedge funds). During periods of stress, this contraction intensifies. Large inflows of deposits further strain leverage ratios, and if raising external capital is prohibitively expensive, banks will curtail market-making and liquidity provision to preserve capital. The result is a procyclical feedback loop: as market stress deepens, the institutions best equipped to stabilize liquidity - banks and primary dealers - retreat, amplifying volatility and system-wide risks. This helps explain the events of April 2025, which essentially pushed me to put together this 'x-ray' of how the US Treasury market (and the “new” financial system) functions today.

In this direction, as the role of banks has relatively diminished, into this vacuum have stepped Principal Trading Firms (PTFs), whose rise has been both a response to and a reflection of constrained traditional bank intermediation. PTFs operate under vastly different models than banks. They trade on their own account and deploy short-term, automated strategies, focusing on rapid-fire transactions in highly liquid, on-the-run Treasury securities. However, because PTFs are not members of the Fixed Income Clearing Corporation (FICC), their trades typically settle bilaterally and remain outside the central clearing system (so far). The same holds for much of the dealer-to-customer segment - which includes hedge funds, asset managers, and pension funds - where trades also settle bilaterally via clearing banks. As a result, only a small share of Treasury cash transactions - just over 10 percent in recent years - has been centrally cleared. In the figure below we can see the composition of dealer position in repo and reverse repo transactions.

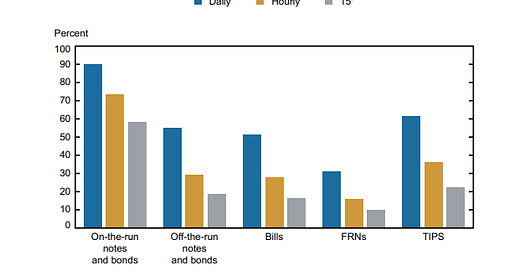

For those who may not be familiar, on-the-run Treasuries are the most recently issued US government securities of a given maturity (e.g. the most recent 10-year note), while off-the-run Treasuries are older issues of the same maturity that are still outstanding but no longer the latest. On-the-run securities are far more liquid, trade at tighter bid-ask spreads, and are the benchmark instruments used for pricing and hedging in financial markets. The fact that PTFs concentrate their activity in the on-the-run market is significant because it reflects their reliance on high-frequency, low-margin strategies that require deep liquidity and minimal market impact. While this boosts efficiency and price discovery in the most liquid segment of the Treasury market, it also means that PTFs largely ignore off-the-run securities - where liquidity is thinner and more reliant on traditional dealers. This bifurcation contributes to fragility in stressed environments, when liquidity can quickly vanish.

As such, unlike primary dealers, PTFs do not maintain significant inventory or client-facing obligations, nor are they subject to the same capital regulations. Their dominance in electronic platforms - especially central limit order books (CLOBs) - means they now account close 60% of trading volume in the interdealer Treasury market (for 10-year on-the-run notes), up from negligible levels two decades ago. In this market, bank dealers’ and broker dealers' share is only 34.7%, the rest being split among non-bank dealers and hedge funds. Why CLOBs? Because CLOBs match buy and sell orders based on specific rulesets, enabling ultra-fast trade execution (as soon as the buy and sell orders are matched). This structure aligns perfectly with the high-speed, algorithmic strategies deployed by PTFs.

As such, while PTFs have enhanced day-to-day liquidity in normal times, their presence brings structural vulnerabilities. We have seen that they are typically not members of the FICC, meaning most of their trades are uncleared and settled bilaterally. Moreover, their business model is not designed to absorb or lean against shocks; in times of market stress, PTFs reduce participation or exit altogether, unlike dealers who are expected to continue making markets even in volatile conditions. This has led to increasing concerns about fragmented liquidity, particularly for off-the-run Treasuries, where PTF activity is sparse and dealer intermediation remains essential. This is essentially the same issue we've been discussing over the past few days: the growing role of hedge funds and prime brokers - especially in the US Treasury market - which, while seemingly adding complexity, actually increases fragility, given how leverage-intensive these institutions are.

Recognizing the mounting systemic risks posed by this market bifurcation - where a growing volume of Treasury trades occurs outside of clearing mechanisms - the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) introduced a landmark regulatory shift in December 2023 (which is set to continue until June 2026). The new rule mandates central clearing for certain secondary market Treasury transactions, including Treasury repo.

By requiring that more trades clear through Covered Clearing Agencies (CCAs), the SEC aims to extend the benefits of central clearing - risk mutualization, transparency, and operational resilience - to a broader swath of market participants, including PTFs and hedge funds. The phased compliance deadlines will fundamentally reshape the market’s architecture and impose new demands on participants to upgrade infrastructure, establish clearing relationships, and integrate into centralized systems.

As such, to continue trading (in) US Treasuries via interdealer brokers (IDBs) after December 2025, hedge funds and PTFs will be required to centrally clear their transactions. More specifically, by the time these new rules are fully implemented - expected around June 2026 - it is anticipated that most, if not all, repo and reverse repo transactions will be centrally cleared for hedge funds, money market funds (MMFs), and asset managers (with the exception of certain public entities such as the Federal Reserve). The same applies to interdealer transactions executed on IDB platforms, and the designation of most PTFs as broker-dealers supports this transition.

To comply with this new clearing mandate, PTFs must either become direct participants in CCAs - if eligible - or clear through an intermediary such as a bank, broker-dealer, or futures commission merchant (FCM), as discussed at great length here. While hedge funds and PTFs will seek cost-effective and efficient solutions, their ability to stay active in the market depends on whether clearing services meet their operational and margin needs.

If suitable options are unavailable, there’s a real risk that some firms could exit the Treasury cash market. Since PTFs are key liquidity providers - especially in on-the-run Treasuries - their withdrawal could reduce market depth, raise volatility, and tighten repo conditions. Ensuring continued participation beyond December 2025 will require addressing structural gaps in clearing access and adapting infrastructure to support a wider range of market participants.

In sum, the binding nature of leverage ratios like the eSLR has curtailed bank-based intermediation in the Treasury market, paving the way for PTFs to dominate liquidity provision (in some aspects). Yet their short-term orientation and structural limitations have prompted regulators to respond. The SEC’s clearing mandate represents a critical attempt to rebuild stability and resiliency in a market that underpins the global financial system. The question is - will it succeed? It will be interesting to observe how incentives and the behavior of hedge funds and PTFs shift in the coming months, and whether we might reach a point where they begin to pull back. It’s unlikely, but the financial system has seen bigger surprises before.

Alex, an excellent description of what currently appears on the horizon. However, I would suggest that the Treasury and Fed are both aware and before long we are going to see SLR restrictions on banks relaxed or removed to allow more activity by the banking sector and eventually I suspect we will see mandates for banks and insurers to own a certain percentage of Treasuries on their balance sheets. Someone also suggested that in 401K's, IRA's a minimum percentage of Treasury ownership will be required to maintain the tax advantages.

I don't believe we will get to the point where there are real problems as they will simply change the rules to alleviate them.