Last week, the Federal Reserve released the results of its annual stress tests on the 22 largest US banks. As expected, all banks passed. The test projected some $550 billion in hypothetical losses across these institutions, yet each remained above the minimum capital thresholds required to continue lending, paying dividends, and operating normally. The headline takeaway? The banking system is “well capitalized” and “resilient to a range of severe outcomes,” according to Michelle Bowman, the Fed’s new Vice Chair for Supervision.

At first glance, this seems reassuring. But a closer look reveals that these stress tests are losing analytical relevance just when we need them most.

The first issue lies in the stress scenario itself. Compared to 2024, this year’s hypothetical crisis was notably milder: unemployment peaks at 10%, housing prices fall 33%, and commercial real estate drops 30%. That might still sound dramatic, but in 2024, the modeled housing decline was 36%, CRE was set at -40%, and stocks dropped 55%. The Fed’s explanation for dialing back the pain? Previous tests had caused “unintended volatility” in results. Going forward, the Fed says it plans to seek public comment to improve the consistency and design of the test.

But consistency is not the same as credibility. These stress tests are meant to be precisely that - stressful. The idea is to probe the system’s resilience in the face of the unexpected, not to offer a relatively comfortable scenario that almost guarantees a pass. What we’re left with is an exercise that offers the optics of stability but not necessarily its substance.

This brings us to the second problem: the capital ratios themselves. While all tested banks held capital well above regulatory minimums, their Common Equity Tier 1 (CET1) ratios hover around levels that - ironically - Lehman Brothers also held before its collapse in 2008. For instance, the common equity Tier 1 ratio for bank holding companies (BHCs) with assets over $750bn currently stands slightly above 12.5%. By comparison, Lehman Brothers - just before the official outbreak of the Global Financial Crisis - increased its Tier 1 capital ratio from 10.7% at the end of Q2 2007 to over 11% at the end of Q3 (source here) (One point here - It is well known that CET1 ratio and Tier 1 capital ratio are not identical - since the latter includes additional Tier 1 instruments - but Lehman Brothers was not required to disclose a CET1 ratio at the time and only Basel III introduced CET1 as a distinct, stricter capital measure after the crisis: so this comparison is made here to provide a rough benchmark of capital quality relative to today’s standards).

Even more striking, the same source shows that Lehman’s total stockholders’ equity rose by $2.1 billion in that quarter, from $26.3 billion to $28.4 billion. To be clear, this is not to suggest that today’s banks are in a Lehman-style situation, far from it. But the point is that capital ratios alone are not sufficient to assess the resilience of the banking system.

Source: Bank Policy Institute

It’s also true that none of the risk calculations applied to Lehman Brothers came from a formal stress test conducted by the Federal Reserve or the SEC. Investment banks like Lehman relied on internal tests and those tests were not standardized, lacked systemic assumptions (e.g. liquidity crises), and often assumed that markets would continue to function normally even in a downturn. Lehman Brothers, as a stand-alone investment bank, was regulated by the SEC under the Consolidated Supervised Entity (CSE) program, not the Fed. And the same CSE program was widely criticized after the crisis for failing to detect rising leverage and liquidity risk.

But the collapse of Lehman Brothers, the near-failure of many other institutions, and the widespread erosion of confidence in the banking system exposed a critical regulatory blind spot: large banks could be undercapitalized and overly exposed to risks that didn’t show up in regular financial statements. In response, US regulators -led by the Federal Reserve - developed a new framework for testing the resilience of the banking system. Two major tools emerged from this post-crisis regulatory overhaul: the Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review (CCAR) and the Dodd-Frank Act Stress Test (DFAST). In that sense, we can say the current framework may be closer to reality today than it was back when financial institutions relied exclusively on internal risk models.

But here’s the kicker: the Fed’s stress-testing framework does evolve but usually only after a crisis exposes its blind spots. These tests didn’t prevent the Credit Suisse-Archegos debacle. For those unfamiliar with the episode, I’ll briefly explain what went wrong and why it still matters.

When Archegos Capital Management collapsed in March 2021, it inflicted multi-billion-dollar losses across some of the world’s largest financial institutions. Nomura lost $2.85 billion. Morgan Stanley took a $911 million hit. UBS wrote down $861 million. But it was Credit Suisse that suffered the most, absorbing a $5.5 billion blow that would mark the beginning of the end for the bank. The underlying cause was a relatively plain, legal, and widely used financial contract: the equity total return swap (TRS).

A TRS is a bilateral derivative in which one party receives the total economic return - both price movements and any dividends or distributions - on a reference asset, typically a stock or a basket of stocks. In return, the receiver pays a financing rate, often a floating rate like SOFR plus a spread, to the counterparty, usually a prime broker or dealer (more about here). In more detail, in a typical TRS structure, a bank (like Credit Suisse) buys a stock (say, ViacomCBS) on behalf of a client (Archegos). Archegos does not appear on the shareholder register. The bank legally owns the shares. Through the swap contract, Archegos receives the economic gains or losses associated with the stock’s performance (price changes and dividends). If the stock goes up, the bank pays Archegos the gain. If it goes down, Archegos must compensate the bank for the loss (through a margin call).

As such, this mechanism is central to what is known as synthetic prime brokerage. Instead of borrowing money to buy shares in a margin account, hedge funds or family offices can enter into a TRS with a prime broker. The fund posts initial margin - often just a fraction of the notional size of the position - and receives the total return of the referenced equity.

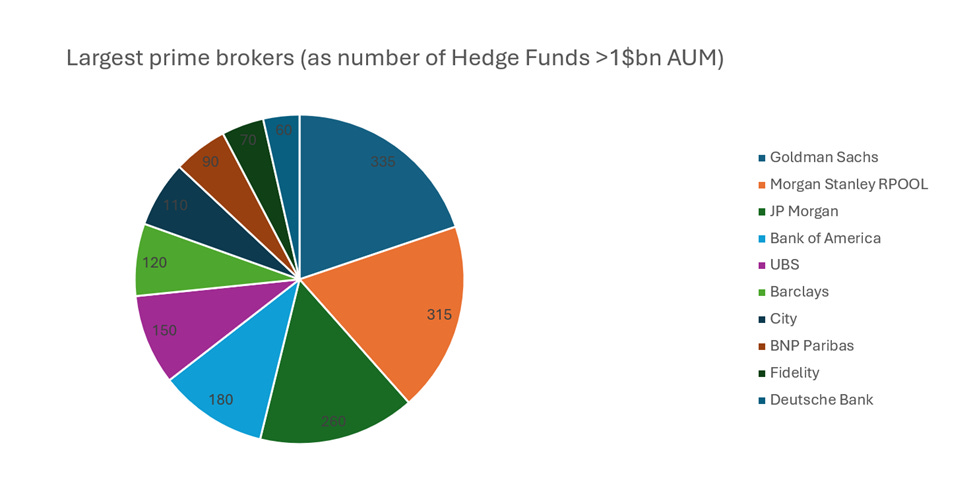

Why does this matter? There are two main reasons. First, the stress test results themselves (again). According to the report, “aggregate losses from the assumed default of the hedge funds are moderate, amounting to roughly $8 billion”. The report further clarifies that this component “applies stresses to valuations of single-name US equity exposures held by hedge fund counterparties,” which once again brings to mind TRSs, as discussed earlier. This raises two immediate observations. The first: it’s unclear how the estimate of just $8 billion in potential losses was calculated. As previously discussed, the relationship between prime brokers and hedge funds remains deeply intertwined. As discussed above but also illustrated in the chart below, Goldman Sachs alone maintains relationships with over 335 hedge funds managing more than $1 billion in assets. If we include all hedge funds - those below the $1 billion threshold as well - data from the Bank for International Settlements indicates that Goldman Sachs is linked to roughly 1,200 hedge funds.

Source: Author’s illustration based on the Withintelligence data

This is relevant especially when we consider that the prime broker–hedge fund relationship is shaped by what’s known as wrong-way risk (WWR), a situation where credit exposure rises precisely when the counterparty’s ability to repay deteriorates.

WWR emerges when a prime broker’s exposure to a hedge fund increases precisely when the fund’s likelihood of default also rises. In other words, the counterparty becomes riskier at the worst possible time, just as the broker’s credit exposure peaks. This dynamic is amplified by opacity: prime brokers frequently lack full visibility into a fund’s aggregate positions, especially when exposures are spread across multiple banks, involve complex instruments, or rely on internal fund valuations that may not be independently verified.

The Archegos collapse provides a textbook example. The fund built highly leveraged, concentrated positions through equity total return swaps with several prime brokers. Each broker, seeing only its own exposure, failed to grasp the scale of Archegos’s aggregate risk. When the underlying stocks declined, Archegos’s solvency deteriorated just as the banks’ exposures ballooned, a classic case of WWR. But this pattern isn’t unique to Archegos. The hedge fund sector as a whole displays signs of procyclical leverage: prime brokers tend to ease lending terms and increase credit provision when markets are rising, only to tighten conditions abruptly during downturns. Secured borrowing by hedge funds moves in tandem with equity valuations, while perceived creditworthiness deteriorates during selloffs, precisely when margin loans are most exposed to losses. In this context, how can we still talk about “potential” losses of just $8 billion? Any crisis of confidence, followed by a liquidity squeeze, can trigger a cascade of margin calls that snowball into something far more destructive.

But that’s not the core issue. As I mentioned earlier, it took the Credit Suisse–Archegos shock for the Fed to even begin incorporating the bank–hedge fund nexus into its stress-testing framework. And even then, the treatment remains superficial: in today’s report spanning over 60 pages, hedge funds are mentioned only ten times.

Which leads us to the current elephant in the room: private credit.

Private credit - a loosely regulated, rapidly growing $2 trillion market - is nowhere to be found in this year’s stress test design. This despite the fact that even the Fed’s own regional banks, including the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston (this report was published in May this year and you can read it in full here), have warned about the systemic vulnerabilities tied to private lending. These loans, extended largely by nonbank institutions, often operate in illiquid markets and under looser underwriting standards. The sector has become a magnet for yield-hungry investors, while simultaneously embedding itself in the funding pipelines of corporations across the US. I’ve discussed this topic in more detail here. In that piece, I also noted that, according to the IMF’s 2025 Global Financial Stability Report, over 40% of borrowers in the direct lending universe now operate with negative free cash flow and many are reliant on payment-in-kind (PIK) interest, “amend-and-extend” restructuring clauses, and flexible covenants that mask underlying distress. Equally, global banks have extended over $500 billion (!) in credit facilities to private credit funds, equating to roughly 25–30% of global private credit AUM. It’s true that banks seek to mitigate - or rather, offload - this risk through Synthetic Risk Transfers (SRTs), structures that allow them to keep the asset on their balance sheets while transferring the associated credit risk to third-party investors, often insurance companies, pension funds, or credit-focused investment vehicles. But this risk doesn’t vanish, it merely shifts onto the balance sheets of those institutions. In other words, SRTs do not eliminate credit exposure. These instruments repackage and redistribute it across the financial system. And in the event of a systemic shock, correlation risk can render these protections ineffective. We’ve seen this before: CDOs, CLOs, private-label MBS, and even square CDOs were all originally designed to spread risk until they concentrated it, catastrophically, in 2008.

What happens when private credit goes through its first real credit cycle? What happens when defaults spike, valuations collapse, and these opaque exposures begin to boomerang back onto the balance sheets of large financial institutions through warehousing facilities, equity co-investments, or indirect contagion?

The Fed’s silence here is troubling. Not only did it fail to simulate private credit shocks, it didn’t even mention them in the methodology or accompanying reports. Some might argue that private credit assets sit mostly outside the regulatory perimeter and therefore lie beyond the Fed’s stress-testing mandate. But this misses the point. The whole purpose of stress testing is to imagine how seemingly “external” risks might permeate the core of the financial system. That includes indirect channels of transmission - from asset price volatility to funding market stress - and feedback loops triggered by nonbank instability.

We don’t need perfect foresight. But we do need a willingness to acknowledge the next likely source of instability, especially when it’s growing at double-digit rates and has already become integral to corporate finance.

At its best, the stress test is a tool for anticipation, not justification. A test that everyone is expected to pass is more of a branding exercise. The Fed has a difficult task in balancing market confidence with regulatory vigilance. But the credibility of the stress-testing framework depends on its ability to evolve ahead of the curve, not behind it. That’s why I can only hope the Fed won’t need to update its stress-testing framework in the style of Credit Suisse–Archegos, meaning in the wake of a financial shock…

Elefant indeed. Everyone knows the risks and we still play the game until the fat lady sings