The April 2025 Bank Lending Survey confirms what many suspected but few wanted to admit, that the lending landscape remains clouded by risk aversion, economic uncertainty, and eroding credit quality. It’s exactly what I expected would happen, as I pointed out here before. Credit standards for firms tightened once again, albeit slightly, continuing a cautious trend that’s persisted through multiple quarters (see Figure 1). Despite expectations for some relief, banks remain deeply concerned about deteriorating firm-level conditions and the increasingly volatile macroeconomic outlook. An even greater concern is that these tighter credit standards are emerging right at the core - in Germany and France, the so-called economic engines of Europe. And when firms in the European core start to struggle, it rarely stays contained. Sooner or later, the (European) economy as a whole tends to follow the same downward path.

Figure 1. Changes in credit standards for loans and/or credit lines to European companies

Source: ECB

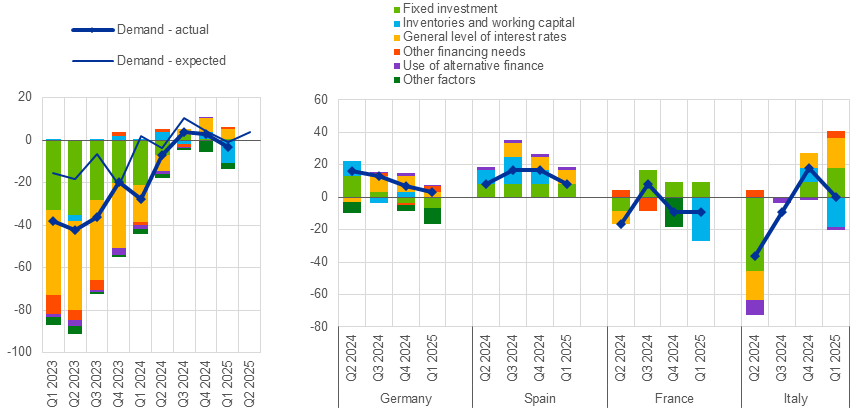

Perhaps more concerning is the retreat in demand for credit. After two quarters of timid resurgence, firms are once again pulling back on loan requests. This time, the decline is driven not by interest rates - which are continually falling - but by collapsing working capital needs and shrinking inventories. This weak demand is also closely tied to the new lending standards. Firms - faced with shrinking inventories and reduced capital needs (which, in turn, reflect both sluggish consumer demand and deep uncertainty about long-term projects) - are increasingly realizing that banks have become far more selective. And when capital needs are already low, the logical next step is to opt out of borrowing altogether.

Figure 2. Changes in demand for loans and/or credit lines to European companies

Source: ECB

In short: firms aren’t borrowing because they aren’t building, producing, or expanding, and banks, in turn, are growing ever more cautious. Even cheap money can’t tempt demand when business sentiment is this subdued. This is particularly true for banks now operating in a low-interest-rate environment where profit margins are already compressed. And really, who wants to take on more risk for even less reward?

So the old question re-emerges: Can central banks truly stimulate the real economy?

If you’ve been following this blog for a while, you already know the answer: Not really.

Meanwhile, the housing market is enjoying what appears to be a moment of strength. Credit standards for mortgages have eased and demand continues to climb. But this is a recovery fueled more by competition among banks than by genuine economic optimism. Underneath it all, risk perceptions remain elevated, and lenders quietly report increasing concerns about the quality of loans on their books. The strong appetite for housing credit might mask a deeper issue - banks reaching for volume to compensate for narrowing margins, knowing full well the quality of borrowers is slipping.

What little relief banks received on funding conditions - from money markets or securitisation channels - is counterbalanced by the ECB’s ongoing policy normalization. As the central bank quietly shrinks its balance sheet, liquidity dries up. Profitability is being squeezed from both ends: declining net interest margins and rising provisioning needs. And though asset volumes are slowly ticking up, they’re not enough to offset the profitability hit banks expect over the next six months.

Moreover, the ECB’s ongoing quantitative tightening - essentially the shrinking of its balance sheet through the halt of reinvestments in maturing bonds - is “pushing” banks to absorb newly issued government debt onto their own balance sheets. This dynamic reduces the balance sheet flexibility banks typically rely on and ultimately leads to a crowding-out effect on private sector lending. Of course, banks are not doing this just because they have to. In today’s increasingly uncertain environment, government bonds remain one of the few “safe” assets available. For many banks, this is also a strategic retreat, a shift toward lower-risk exposures at a time when broader credit conditions are deteriorating (this is something I already discussed here). But the consequence is clear: more sovereign debt on bank balance sheets means (or could mean in the future) less room for private credit, and another brake on already weak lending momentum.

In essence, the euro area’s credit pulse is flickering - but hardly stable. The short-term uptick in mortgage demand may offer a fleeting mirage of health, but the underlying picture remains bleak. Credit quality is deteriorating, firms are retreating, and banks are tightening - not loosening - the very channels that should be fueling recovery.

Europe’s lending recovery? It’s a recovery in name only - a house of cards built on cautious optimism, already trembling at the base.