The German Bund has historically been the cornerstone of the European sovereign bond market. As a high-quality, liquid, and low-risk instrument, Bunds have long served as both a benchmark and a preferred hedge for fixed income portfolios and swap structures across the Eurozone. However, recent developments in European interest rate swap spreads - especially in November 2024 - and constitutional reforms are gradually reshaping the role of Bunds. In other words, the fixed leg of 10-year euro interest rate swaps trading below the nominal yield on the German bund for the first time in history and the growing importance of EU supranational bonds raised questions about whether Bunds will remain the dominant hedge instrument in European interest rate markets.

This becomes truly important in the context of the removal of the “debt brake” and the increase in investments in defense and infrastructure. Not from the perspective of rising aggregate demand or enhanced defense capacity, but rather from a less studied angle, the hedging role of these instruments.

I have already discussed the issue of negative swap spreads in the case of the United States, where they are primarily linked to structural changes in funding markets and the transition from LIBOR to SOFR (a risk-free rate), among others. However, for greater theoretical clarity, this analysis will also examine the same phenomenon in the case of euro-denominated instruments, which have received far less attention in this context.

So I start with a crucial question: why have euro swap spreads turned negative?

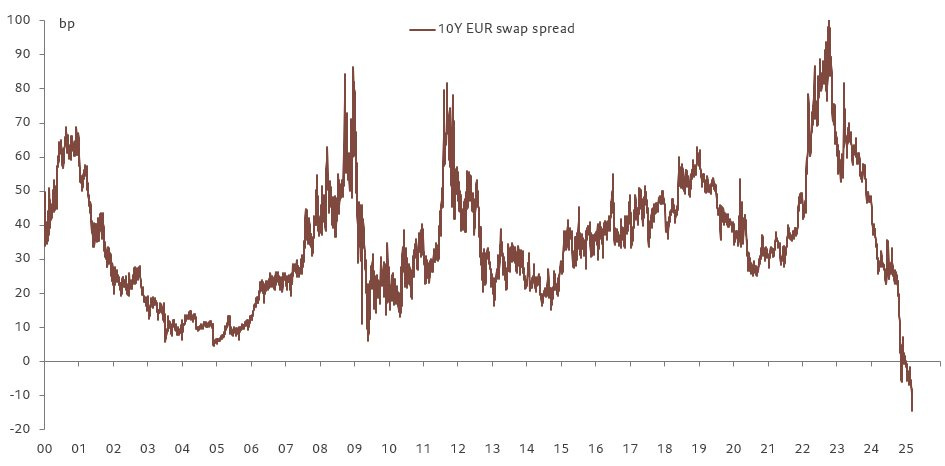

Negative swap spreads - where fixed rates in interest rate swaps fall below the yield of corresponding government bonds - have become a structural feature of European financial markets in the last year. While such negative spreads became familiar in the US post-2008, their appearance in Europe came much later, driven by a combination of technical, structural, and macroeconomic factors.

The first key factor is the end of the Eurosystems’s Asset Purchasing Programme (APP), or Quantitative Easing (QE) - terms I consider functionally equivalent - and the subsequent decline, if not disappearance, of the so-called bund “scarcity premium”. More specifically, the Eurosystem’s post-Eurocrisis QE programs, particularly the Public Sector Purchase Programme (PSPP), created an artificial scarcity of Bunds by crowding out private investors. As the Eurosystem absorbed a substantial portion of outstanding German government debt, Bunds began to trade at a pronounced “scarcity premium” - something we have analyzed in the co-authored research paper on repo transactions. However, with the cessation of net purchases and the initiation of balance sheet reduction in 2023–2024 - the so-called Quantitative Tightening (QT) - more Bunds have been released back into the market. This reversal has eased the “scarcity premium” and played a central role in the eventual inversion of euro swap spreads (from positive to negative).

Another important factor is represented by the changes in the banking intermediation and in the market structure as a whole. In more detail, the structural underpinnings of swap spreads have also shifted. In the past, positive spreads reflected the credit risk embedded in floating leg benchmarks like EURIBOR. Post-crisis, the increase in the use of ESTER for the floating leg has removed much of this risk component. Meanwhile, regulatory constraints - especially those introduced via Basel III - have made holding government bonds more attractive for banks than engaging in swap intermediation. This imbalance in supply and demand has compressed swap spreads further.

Last but not least, another difference is the comparative lag in the ECB’s monetary policy. Compared to the US, the ECB’s post-crisis pivot to normalization came later and more cautiously. While the Federal Reserve began hiking rates aggressively in 2022, the ECB followed more gradually.

In addition, European corporations have become increasingly active in the interest rate swap markets, seeking to manage their interest rate exposure stemming from corporate bond issuance - a trend also observed among pension funds and insurance companies. To complete the picture, repo rates shifted significantly with the onset of QT, making it cheaper to borrow Bunds through repo transactions as the scarcity premium gradually disappeared.

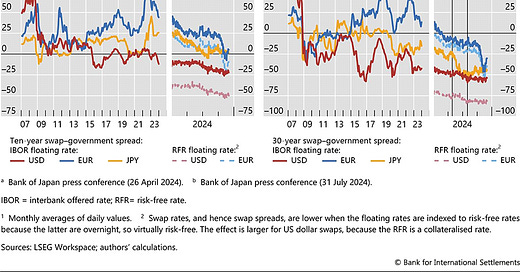

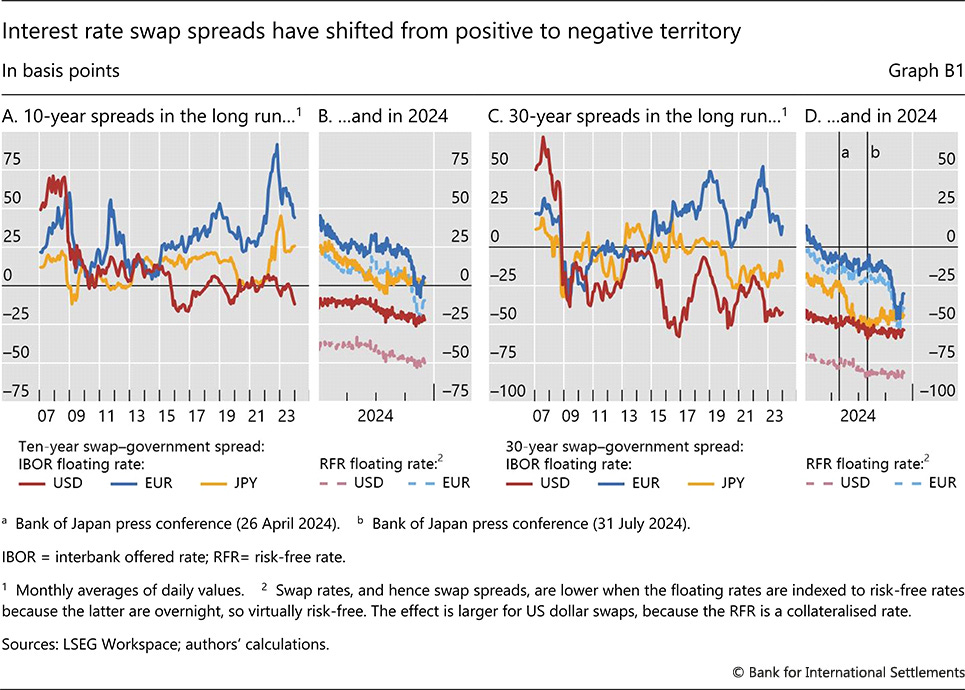

All of this - particularly QT - has prompted the private sector, especially the banking system, to absorb the government bonds “released” through the central bank’s balance sheet reduction. However, this private demand is inherently more volatile and less predictable than official sector absorption. As a result, a net supply of Bunds has returned to the market (at a time when demand is no longer primarily driven by the Eurosystem and corporate entities are making more intensive use of the swap markets). The outcome? Yields on Bunds have risen and this dynamic has also affected swap spreads. As illustrated in the BIS chart below, swap spreads in the euro area have turned negative - both at the 10-year and 30-year maturities (close to the end of 2024).

Source: Bank of International Settlements

This QT also explains why the use of the ECB's Securities Lending Facility has declined and why private markets’ balance sheets now hold a record amount of government bonds, especially European banks (since November 2024).

As argued before, similarly to the United States, European banks are also significantly affected by regulatory constraints. Although European repo markets remain essential - and banks lie at the core of these markets - these institutions must cover counterparty risks not only through collateralization but also by complying with leverage ratio constraints. In particular, G-SIBs are required to meet regulatory capital requirements based on the nominal value of a transaction (for exposures that are not cleared with a clearing house). This latter factor plays a considerable role in shaping how financial institutions can engage in arbitrage strategies that influence swap spreads.

At the same time, interest rate futures in Europe are often linked to specific national debt instruments, making them sensitive to country-specific fiscal dynamics. In that vein, they are generally less effective for hedging Eurozone-wide interest rate exposure compared to interest rate swaps (IRS) (hence the higher demand for European and foreign corporates). This explains the tighter correlation between the interest rate swaps levels and monetary policy developments, but also why their prices are pushed even more negative.

But this is where the importance of Bunds comes in. We’ve seen that several factors contributed to the emergence of negative swap spreads in the Euro Area. However, what truly captured attention was the transformation of Bunds - namely, the fixed leg of 10-year euro interest rate swaps trading below the nominal yield on German Bunds, back in November last year.

This situation reoccurred in March 2025, as debates over the removal of the “debt brake” came to a close.

This brings us to the next question: are Bunds still the best hedging instruments for euro-denominated positions? For decades, Bunds have served a dual purpose, acting both as the benchmark for pricing Eurozone debt and as the primary hedge for swap and duration risk. But both of these roles are now facing subtle, yet significant, challenges, as already noted elsewhere.

While Bunds remain the benchmark of choice due to their perceived safety and liquidity, the evolving political landscape of the Eurozone increasingly complicates this position. The removal of the constitutional debt brake in Germany has sparked renewed debate over the country’s fiscal trajectory, culminating in expectations of increased issuance, driven by new spending commitments on defense and infrastructure. Why does this matter? Because it undermines the Bund’s scarcity value, with direct implications for existing hedging models. A relatively abrupt shift - within less than a year - from a scarcity premium to a (potential) growing abundance of such collateral fundamentally alters the structure of funding markets and, by extension, the cost of hedging (because these investments will lead to a different yield than usual).

Meanwhile, spreads on peripheral bonds - such as those of Italy, Spain, and Portugal - tend to widen under stress, rendering them unsuitable as hedging instruments due to their credit volatility. This dynamic was clearly demonstrated during the Eurocrisis. In such a context, relying on a basket of European government bonds for hedging purposes becomes unworkable.

Precisely for this reason, discussions surrounding supranational EU bonds have intensified, not as instruments that could replace US Treasuries, as initially assumed (a view I have critically rejected as unrealistic here), but rather as instruments whose role as hedging tools may expand. In more detail, since the launch of the EU’s SURE program and the €750 billion NextGenerationEU (NGEU) initiative, EU-issued supranational bonds have grown in both size and importance. These bonds, backed by the EU budget and shared fiscal guarantees, have introduced a pan-European asset class that could rival Bunds in duration hedging and pricing functions.

Unlike national sovereigns, EU bonds carry less political fragmentation risk and offer a more centralized fiscal narrative (being backed by the EU budget through a unified funding approach - more on that here), especially appealing to non-Euro investors seeking Euro duration exposure. Importantly, they are increasingly liquid and widely held by central banks, investment funds, and international reserve managers. As issuance ramps up, EU bonds may become the preferred asset for hedging euro swaps, particularly if they become embedded in collateral frameworks and benchmark indices.

This is precisely why the role of German Bunds as the primary hedge for euro swaps is now being called into question. As the constitutional limits imposed by the debt brake are de facto dismantled, German bonds are no longer seen as the unequivocal go-to hedge instrument, especially as their pricing will adjust to increased issuance volumes. In this context, EU Bonds have started to be viewed as a more effective hedge not only for euro swaps but also for other government securities. For instance, in November, when swap spreads turned negative, EU Bonds exhibited a 0.96 correlation with Bunds, while swaps versus Bunds showed a 0.93 correlation.

Yet a crucial question remains unanswered: how can EU Bonds be considered reliable hedging instruments when they are fundamentally temporary in nature and lack the political will required to become permanent features of the Eurozone’s architecture? That permanence would require treaty changes far too complex and politically unfeasible under current conditions. For now, we are left with incomplete solutions.

While markets may be captivated by the prospect of new defense spending and infrastructure investment, there is a less discussed negative consequence: the erosion of the scarcity premium on Bunds and the implications for hedging strategies. This post will likely open the door to further discussions on this Substack blog about how hedging might evolve in an era of abundant German collateral and the transience of EU Bonds. Stay tuned!