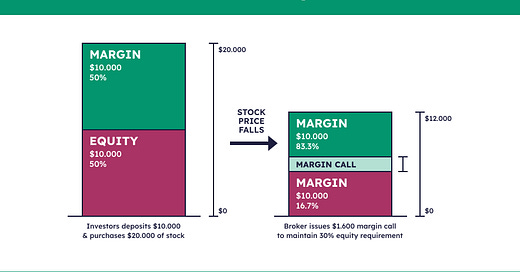

Modern derivatives markets rely on the systematic exchange of collateral to manage counterparty risk. This is typically done through two key mechanisms: initial margin (IM) and variation margin (VM). Initial margin is posted at the outset of a derivatives contract to cover potential future exposure - i.e., the risk that one party defaults before the contract is settled. Variation margin, by contrast, is exchanged daily (or more frequently) to reflect changes in the market value of the contract - essentially a mark-to-market settlement (this applies to margin calls, which are triggered when falling prices reduce account equity below required levels). Both IM and VM apply to cleared transactions (processed through central counterparties, or CCPs) and to non-cleared bilateral transactions (governed under ISDA Credit Support Annexes), though the rules and thresholds vary. Since the 2008 financial crisis, global regulators have increasingly mandated collateralization of derivatives exposures - whether centrally cleared or not - pushing institutions to manage margin in more complex and systematic ways.

Figure 1 below shows a simplistic overview of a variation margin:

Source: Highstrike

Over the past decade - and with renewed urgency since the onset of the pandemic - this collateral ecosystem has undergone a fundamental transformation. What was once a margining system dominated by cash, especially for VM, is now shifting steadily toward a more diversified structure where non-cash collateral plays a more important role. For instance, according to ISDA’s 2025 Margin Survey, the total amount of initial and variation margin collected for non-cleared derivatives reached $1.5 trillion at year-end 2024, a 6.4% increase from 2023. This growth was driven almost entirely by VM, which rose 9.3% to $1.0 trillion, while IM remained flat at $431.2 billion. Regulatory VM increased by 13.3% to $744.5 billion, while discretionary VM held steady at $283.3 billion.

On the posting side, participants posted $706.7 billion in VM (down 3.6% from 2023), including $514.4 billion in regulatory VM and $192.3 billion in discretionary VM. What is really important is the fact that the composition of VM collateral is gradually shifting away from cash. Cash still dominates, but its share fell to 68.3% in 2024 (from 80% in 2020), while government securities rose to 17.8% and other securities to 13.8% -the highest since ISDA began tracking. Moreover, the cash share has decreased for the fourth consecutive year.

This diversification is more pronounced in discretionary VM (that is voluntarily collateral posted for non-cleared derivatives), where only 58.5% was posted in cash, compared to 72.0% for regulatory VM. Overall, received VM collateral was composed of 51.3% cash, 28.7% government bonds, and 20.0% other securities, marking a continued trend toward non-cash collateral in margining practices.

Source: ISDA

This change has been shaped by high-profile episodes of market stress, shifts in regulatory architecture (especially supplementary leverage ratio), and the operational expansion of collateral platforms that facilitate more flexible margin management (such as JPMorgan, Euroclear, BNY Mellon). Understanding this evolution requires retracing the sequence of events and structural pressures that made the old system untenable.

The dash-for-cash in March 2020 was a key inflection point. As the COVID-19 pandemic triggered an abrupt global market sell-off, participants across the financial system scrambled to meet large, unexpected VM calls. Given the dominance of cash collateral in VM, many institutions were forced to liquidate assets, particularly US Treasuries and other high-quality liquid securities, to raise the necessary cash. This created a negative feedback loop: the more Treasuries were sold, the more their prices dropped, amplifying margin calls and worsening the liquidity crunch. Central banks, especially the Federal Reserve, intervened on an unprecedented scale to stabilize market functioning. This is the dash-for-cash in a nutshell: “In the early weeks of March however – from the 9th to the 18th – a different dynamic took hold; an accelerating ‘dash for cash’ in which, given the illiquidity of other markets, investors sold their most liquid assets, driving safe asset prices down. A dash for cash which turned into a stampede” (as cited in here). The figure below show the dash-for-cash at the beginning of the pandemic crisis (especially during March 2020):

Source: Bank of International Settlements

This event exposed a critical flaw: while cash is the most liquid and valuation-stable form of collateral in theory, its systemic overuse creates liquidity spirals in practice. The dash-for-cash showed that requiring cash VM in turbulent periods creates not stability, but fragility. Since then, there has been a gradual but persistent shift in how market participants think about collateral efficiency and liquidity management.

The 2021 Archegos collapse further reinforced this dynamic. Archegos’ reliance on total return swaps (as we discussed two days ago) meant its prime brokers were exposed to rapid losses when the underlying stock prices fell. Many of these collateral arrangements were bespoke and bilateral, and Archegos’ inability to meet margin calls triggered multi-billion-dollar losses across the Street. While this case stemmed from poor internal risk controls and excessive leverage, it again demonstrated the dangers of thin collateral buffers and bilateral margining that doesn’t scale under pressure.

Then came the UK LDI crisis in September 2022. Following the UK government's mini-budget, long-term gilt yields spiked dramatically. Liability-driven investment (LDI) strategies - used by UK pension funds to hedge long-term liabilities - were highly sensitive to interest rate moves. As yields rose, pension funds faced massive VM calls on their interest rate swaps. Without large cash buffers, they were forced to sell gilts, the very instruments whose yields had triggered the calls, to meet the collateral demands. This created a self-reinforcing spiral of price declines and margin stress. The Bank of England had to step in with a temporary gilt-buying program to stabilize markets. Like the 2020 dash-for-cash, this episode highlighted the dangers of over-reliance on cash in margining systems. More about this event here.

These crises share a common thread: under stress, requiring cash for margin creates systemic liquidity bottlenecks. In this light, we could argue that cash collateral could lead today to large systemic risks. Paradoxical I would say. But why is that? For the buy side - including insurers, corporate treasurers, and small banks - holding large cash reserves is not economically efficient. These institutions typically hold high-quality securities such as sovereign bonds, investment-grade corporate debt, or covered bonds. To meet cash VM calls, they often engage in collateral transformation - that is, they lend out their securities in the repo market to obtain cash. In a classic repo transaction, the institution agrees to temporarily sell a security to a counterparty (usually a dealer) with an agreement to repurchase it later. The cash received can then be used to meet margin calls.

However, post-crisis regulatory reforms, especially the Basel III leverage ratio and liquidity coverage rules, have made repo intermediation more balance-sheet intensive for banks (especially through supplementary leverage ratio, as discussed here, here or here). This has reduced their willingness and capacity to intermediate repo transactions, particularly in times of stress, precisely when the buy side most needs access to liquidity. As a result, collateral transformation via repo has become less reliable, forcing institutions to explore alternatives that allow them to post securities directly as margin, without the intermediate step of raising cash. Hence the systemic risks aforementioned.

This structural tension has propelled the growing use of non-cash collateral, particularly through tri-party collateral platforms, basically as a reaction against the systemic risks that cash collateral present today. These platforms - offered by Euroclear, BNY Mellon, JPMorgan, and others - have historically supported IM arrangements, especially for uncleared derivatives. They are important because tri-party agents perform key operational functions: identifying eligible securities, applying regulatory haircuts, marking collateral to market, handling settlement logistics and so on.

But in recent years, these platforms have expanded to support VM as well. While VM was traditionally managed bilaterally and almost exclusively in cash, the operational feasibility and market acceptance of posting securities as VM has increased significantly. Tri-party platforms now allow buy-side firms to interact with multiple dealers, reduce manual processing, and post a broader range of assets, often from the same pool used for IM or repo.

For example, Euroclear, BNY Mellon, and JPMorgan offer integrated platforms through which a buy-side firm can manage both IM and VM exposures, using non-cash collateral across cleared and non-cleared transactions. This represents a deeper structural response to the fragilities exposed by recent market turmoil. Third-party and bilateral models remain prevalent where the buy side posts cash, but tri-party infrastructure has become essential when firms need to post securities. One important evolution is the effort to enable title transfer of VM collateral within tri-party systems. Under title transfer, the receiving counterparty gains full ownership of the collateral and may reuse it, either to post margin elsewhere or to fund internal Treasury functions. This improves collateral velocity and enhances funding flexibility for dealers. Reuse of collateral - often referred to as rehypothecation (though not entirely identical) - allows institutions to meet margin needs without sourcing new collateral from scratch. For the dealer community, this is particularly valuable, as it helps optimize balance sheet usage and minimize funding costs.

As such, in a nutshell, this diversification is good news -ish. For instance, moving away from a cash-dominated collateral system reduces concentration risk. By accepting government bonds but also equity and corporate bonds, institutions can diversify their collateral pools and better withstand liquidity squeezes, especially during market stress when cash may be hoarded. Moreover, institutions can reserve cash for operational needs or funding requirements while relying on securities for margin obligations. This helps prevent fire sales or sudden liquidity drains, especially for asset managers or pension funds.

Of course, this is not to say that non-cash collateral is ideal. This collateral is still subject to market risks. Government bonds and other securities fluctuate in value, and their use introduces greater exposure to price volatility. During stress, haircuts can rise, triggering collateral calls that may lead to procyclical effects or forced selling. But at the very least, there’s always the possibility of offsetting the loss in value of one non-cash asset with another type of (non-cash) collateral, one that may not be affected by forced selling pressures at that moment. This creates a kind of informal backstop mechanism embedded in the system.

Still, what this really reveals is that (non-cash) collateral is paradoxically today’s cash. And that’s exactly the theme we’ll explore over the coming days here on the blog. The financial system has undergone structural changes that have quietly redefined the textbook roles of its key institutions. Banks now increasingly behave like hedge funds. Hedge funds are deeply involved in the Treasury market. Treasuries produce the collateral that now functions as money. And central banks, more than ever, are stepping into the role of Treasury-like actors, providing collateral backstops during times of stress.

This shift in perspective - this reordering of functions - is the lens we’ll be using in the next few posts. So stay tuned!

Would be interesting to know how the non-cash collateral is actually being treated in times of stress. 🙌