On June 25, the Federal Reserve is set to convene a crucial board meeting, the first under the regulatory leadership of Governor Michelle Bowman, to consider reforms to the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR), a key capital requirement imposed on the nation’s largest banks. While seemingly technical, this prospective change marks a significant turning point in US banking regulation and speaks to deeper tensions at the heart of financial intermediation, sovereign debt management, and systemic stability.

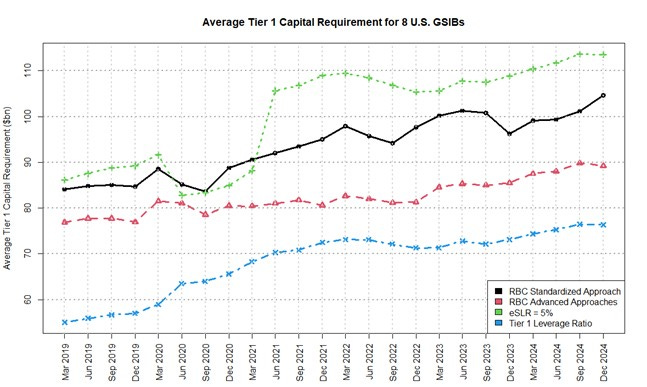

I have covered the SLR on this blog several times before (for example here, here, or here), but given recent developments, it’s worth revisiting the discussion. The SRL ratio was introduced in the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis as part of the Basel III regulatory framework. It mandates that banks hold a minimum amount of Tier 1 capital - currently 5% for globally systemically important banks (G-SIBs) - against their total leverage exposure, regardless of the perceived riskiness of those assets. In contrast to traditional risk-weighted capital requirements, the SLR is deliberately blunt: it treats US Treasuries and junk bonds alike in terms of capital charges (more or less). Below we can see the average capital constraints of 8 G-SIBs.

Source: SIFMA

The intent behind this non-risk-based approach was to create a simple, enforceable backstop to risk-weighted models that were widely gamed prior to 2008. But this simplicity has since evolved into a systemic constraint. As banks have pointed out, the SLR disincentivizes holding-and-trading “safe” but low-yielding assets like Treasuries, effectively punishing banks for participating in government debt markets and hindering their role as market makers, particularly during stress episodes.

The SLR’s impact is particularly evident in the operations of primary dealers, banks that are contractually obliged to underwrite US government debt. Since Treasuries count fully toward leverage exposure, primary dealers face balance sheet constraints that limit their ability to absorb large volumes of government bonds, especially during issuance surges or market turmoil. The March 2020 “dash for cash”, the heavy issuance cycle of 2023–2024, and the dislocations seen around April 2, 2024, all exemplify the SLR’s tightening grip (see more here).

As a result, Treasury market intermediation has increasingly shifted from primary dealers to hedge funds, principal trading firms (PTFs), prime brokers and so on. These entities operate under less rigid capital constraints and are well-suited to execute complex relative value trades like the cash-futures basis trade. But this migration also comes at a cost: it introduces opacity, leverage, and fragility into what was once the most liquid and secure corner of global finance. In essence, the SLR has pushed risk out of the regulated banking sector and into the shadows.

So, the Fed’s upcoming review signals an overdue recognition of these structural inefficiencies. Less than two weeks ago, I proposed here a potential solution (though not a final one or one that would solve all the issues with the SLR). At that time, I said that a balanced approach would involve modifying the SLR into a hybrid model, one that still imposes a leverage constraint but allows for differentiated treatment of low-risk assets. For example, assigning a reduced (but non-zero) capital charge to Treasuries could preserve prudential safeguards while expanding intermediation capacity. Simultaneously, coordination between the Federal Reserve and prime broker-facing institutions should be enhanced to ensure liquidity provision remains robust in moments of stress.

Of course, more practical and politically feasible solutions have also been proposed. For instance, Nellie Liang, Senior Fellow at Brookings Institution argued that making the eSLR leverage buffer countercyclical and exempting central bank reserves from the SLR calculations without reducing the total amount of capital are two options (as described in here). The problem with this countercyclical buffer is that it can be released during periods of market-wide stress, but it must then be “rebuilt” afterward. This rebuilding process can again lead to reduced demand for US Treasuries. Since the volume of these instruments far exceeds what the banking system can intermediate, the problem remains largely the same. The figure below (left) shows how much the US Treasuries market has grown relative to the balance sheets of traditional primary dealers.

Source: International Monetary Fund

Another potential idea is to exempt Treasury securities and central bank reserves from leverage ratio calculations, just as was done during the Covid-19 pandemic, as argued by SIFMA. But that brings us right to the discussion about duration risk. In more detail, there is a risk of simplification. Critics warn that such adjustments may erode the safety buffer the SLR was designed to provide. And here I feel compelled to make a point that might not sit well with everyone. The assumption that Treasuries are “risk-free” is flawed. While free from credit risk, US government bonds are subject to market risk, especially duration risk. The collapse of Silicon Valley Bank in March 2023 is a sobering reminder: SVB’s concentration in government and agency securities, and its failure to hedge interest rate exposure, precipitated a liquidity crisis when those "safe" assets lost value (see more about this here). This is why I have discussed the importance of a hybrid model.

Anyway, this raises a dilemma. Maintaining the current SLR framework may preserve capital discipline but at the expense of market resilience. Loosening it, on the other hand, risks overextending balance sheets and underpricing interest rate risk. That is why it was argued that the reform of the SLR must address this specific risk. The truth is, we’re dealing with a sensitive issue. The only point on which there seems to be broad agreement is that the SLR needs reform. The real debate now is about what form that reform should take.

Ultimately, this debate reveals a deeper truth: that the financial system’s capacity to absorb government debt is increasingly misaligned with the fiscal realities of a high-deficit world. The Fed’s move to revisit the SLR is a recognition that the architecture of post-crisis regulation must evolve to meet the demands of the present.

With global debt/GDP over 3x, there is unlikely any solution that can address both liquidity and resilience issues effectively. No matter the outcome, the weight of excess debt is going to drive the financial system to a worse state