When the Engine Fails: The Story of First Brands’ Bankruptcy and CLOs

When First Brands Group filed for bankruptcy at the end of September, it initially seemed like one of those routine stories you read about every few months, basically a struggling auto parts company, overleveraged after an ambitious expansion, finally running out of road. Nothing to worry about! But within days, analysts and traders realized that this was more than a company-specific failure. If you want, it was another reminder of how fragile parts of the private credit ecosystem still are. But more than that, the bankruptcy also exposed how tightly private credit, collateralized loan obligations (CLOs), and bank-linked financing vehicles have become intertwined (not unlike the hidden plumbing that once made private-label mortgage-backed securities so central to 2008).

At its core, First Brands’ collapse was a balance-sheet story. The company’s total liabilities were officially over $10 billion, but that figure understated the scale of its financing. Like many highly levered corporates, First Brands relied on a dense patchwork of loans, invoice factoring, supply-chain financing, and inventory-backed facilities. A large share of its first-lien debt (roughly $2 billion) ended up inside CLO portfolios across 69 US managers. Deutsche Bank ranked it as the 61st-largest obligor exposure in US CLOs, while Morgan Stanley estimated around €520 million of related loans circulating in European portfolios. Of course, to the casual observer, these numbers might look small. A 0.2% exposure in a diversified CLO hardly sounds alarming. But the real story lies in how the modern credit machine works.

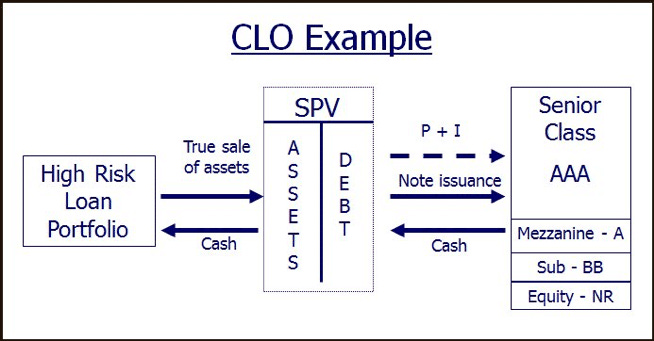

But first, what are CLOs? CLOs are structured finance vehicles designed to repackage pools of leveraged loans (typically extended to highly indebted or non-investment-grade companies) into tranches that cater to different risk appetites. At their core, CLOs operate on a waterfall structure: the cash flows from the underlying loan portfolio are distributed hierarchically, with senior tranches (often AAA-rated) paid first, and junior or equity tranches absorbing losses last. This structure allows risk to be sliced, transformed, and redistributed. The senior tranches attract insurance companies, pension funds, and conservative asset managers looking for relatively safe income streams with slightly higher yields than government bonds. Further down the stack, the mezzanine and equity tranches, where both the risk and potential return surge, are snapped up by hedge funds or private credit vehicles (more about CLOs here).

In essence, CLOs perform a kind of financial alchemy: they take a basket of risky, illiquid corporate loans and convert them into a layered, investable spectrum of securities that can be rated, traded, and used as collateral. This transformation creates liquidity and expands credit supply, but it also embeds leverage and complexity deep into the financial system. Remember the Jenga tower in the movie Margin Call? That’s not far off. And as any financial alchemy, the new issuance of US CLOs is up, as can be seen in the figure below.

Source: Reuters

The question is, does it sound familiar? It should. The structure mirrors the logic of pre-2008 mortgage-backed securities. The difference is that the underlying assets are corporate loans, not mortgages and that, so far, defaults have remained relatively contained. And so, CLOs play a central role in today’s credit markets. They are the main end buyers of leveraged loans, which is debt issued by highly indebted, non-investment-grade companies. Banks originate these loans but increasingly offload them to CLOs, freeing balance sheet space. In turn, CLO managers slice and repackage the loans into securities that can be sold to institutional investors. This feedback loop keeps credit flowing to the riskiest corners of the corporate sector, often beyond the traditional reach of regulated banks. Below is a simplistic overview of a CLO.

Source: Global Financial Markets Institute

That’s where First Brands comes in. The company’s loans were “broadly syndicated”, meaning they were distributed across a wide network of investors rather than negotiated bilaterally. Many of those loans entered CLO portfolios at close to par value. But when the company’s finances began to unravel this summer, prices collapsed to roughly 33 to 36 cents on the dollar. For managers holding these loans, that meant immediate markdowns and for CLOs, it put pressure on overcollateralization (OC) tests, the mechanisms that ensure the vehicle holds enough collateral to protect senior tranches. In more detail, OC tests act as built-in safety checks within CLOs, ensuring that the value of the underlying loans remains sufficient to cover the debt issued. If the collateral value drops too far, these tests automatically redirect cash flows from junior tranches to senior investors, essentially forcing the structure to protect itself when credit quality deteriorates (more about this here).

So far, it is argued that the damage looks “manageable”. Morgan Stanley’s analysis found most CLOs retained comfortable OC buffers, and average exposures were too small to trigger systemic breaches. At the end of the day, the 379 US CLOs holding First Brands debt had an average exposure equivalent to just 0.51% of fund assets and 138 European CLOs had slightly higher exposure at 0.71%. As I said, this are not scary numbers. But the episode showcases two deeper problems.

First, it reveals the limits of transparency in a market that prides itself on diversification. Despite being broadly syndicated, much of First Brands’ financing was opaque, including billions in invoice factoring and inventory-backed loans1 sitting off balance sheet. Those exposures did not appear clearly in the company’s financials until it was too late. Even sophisticated CLO managers and private credit funds were blindsided by the true scale of liabilities.

Second, it highlights how concentrated the system has become. The same handful of banks, such as Jefferies, Deutsche Bank, JPMorgan and so on, underwrite, structure, and distribute much of the leveraged loan and CLO issuance. The same asset managers (Blackstone, PGIM, CIFC ) appear as buyers across multiple tranches. When one large borrower fails, the losses ripple through portfolios held by the same institutions in both the US and Europe.

To be clear, it mirrors 2008, but this is not 2008. CLOs have more conservative structures, with stronger covenants, higher subordination, and no reliance on short-term funding like asset-backed commercial paper. The market has also matured, CLOs today are permanent capital vehicles that cannot be “run on” in the same way as money-market funds or repo-based conduits were (back in the days). Still, the logic of risk transformation remains the same. Credit risk has been repackaged, sliced, and dispersed in ways that obscure where it ultimately sits.

The First Brands case is also a reminder of how idiosyncratic defaults can reveal systemic vulnerabilities. CLOs are designed to absorb individual failures, that’s why they hold hundreds of loans. But a pattern of downgrades across sectors, in this case, auto-related companies facing margin compression and falling demand, can erode those buffers quickly.

Another striking aspect of this episode is the overlap between CLOs and private credit funds. The two are often discussed as distinct, one structured and bank-linked, the other bilateral and flexible. In reality, the line has blurred big time lately. Many private credit funds hold syndicated loans directly or through participations in CLO equity (few weeks ago I discussed, for example, how intertwined life insurers are today with private credit). Some of the same managers who run CLOs also manage direct lending vehicles. That convergence amplifies exposure: when a borrower like First Brands fails, losses hit both the structured and the private sides of the credit spectrum. In other words, there is a convergence that amplifies systemic exposure. When a borrower like First Brands defaults, losses are felt on multiple fronts. For example, CLO investors absorb hits through the structured tranches (see the second figure of this post again), while private credit funds face direct loan impairments. The dual exposure can create feedback loops, distress in one part of the market can quickly influence risk perceptions, valuations, and liquidity across both structured and bilateral private credit channels. In practice, the distinction between “CLO risk” and “private credit risk” has become increasingly porous, making the health of individual borrowers a shared concern across the broader credit ecosystem.

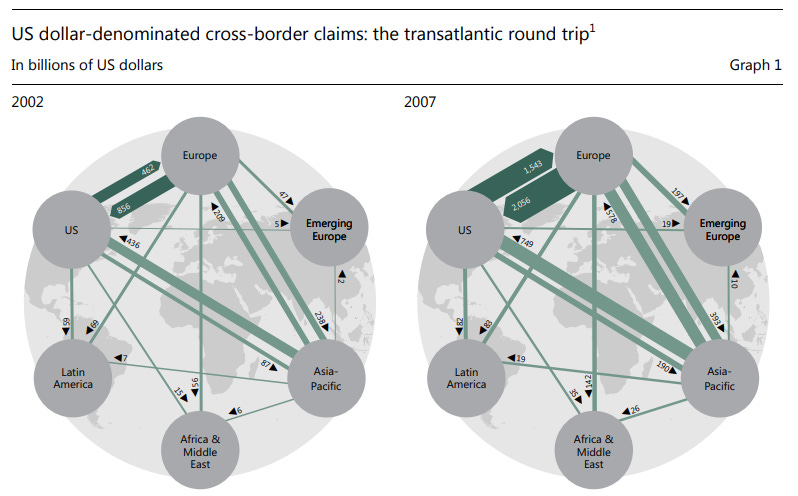

Europe is not insulated either. Around 20 basis points of European CLO collateral was tied to First Brands’ loans, a modest figure, but symbolically important. European managers often rely on the same origination pipelines as their US counterparts. As defaults migrate through the transatlantic leveraged loan ecosystem, European CLOs could face mark-to-market pressure and, over time, tighter refinancing conditions. This is reminiscent of 2007–2008, when the Bank for International Settlements highlighted just how exposed the European banking system was, particularly in USD-denominated assets, to financial instruments originating in the United States (something that can be seen in the figure below).

Source: Bank for International Settlements

Then there is the question of hidden leverage. Off-balance-sheet borrowing, through factoring, supply chain finance, or inventory facilities, allowed First Brands to appear more stable than it was. This practice is not illegal, but it muddies credit analysis. Many of these facilities are financed by private credit funds rather than banks, making them less visible to regulators. When the company filed for bankruptcy, many lenders thought (based on balance sheet that circulated in August) that First Brands had $5.6 billion in corporate debt. But the firm’s bankruptcy filing now estimates liabilities between $10 billion and $50 billion (!). As argued by Reuters, much of the previously unknown debt appears tied to off-balance sheet loans backed by assets (making it almost impossible for First Brands’ primary lenders to recover anything in bankruptcy).

As I discussed several time on this blog (here, here, or here), opacity is the Achilles’ heel of modern credit. Investors rely on model-based estimates of recovery and exposure, but if liabilities are understated, those models can’t capture real risk. CLOs, for all their sophistication, still depend on the accuracy of the underlying data. Of course, as usual, some see a silver lining. For instance, CLO structures worked as intended, absorbing losses without destabilizing funding markets. The junior tranches will take the hit and the senior investors will remain whole. But First Brands bankruptcy revealed how much depends on the assumption that losses remain idiosyncratic and contained. Should defaults cluster across similar sectors, the “manageable” narrative could shift quickly.

If there is a parallel to 2008, it lies not in the instruments but in the mindset. Then as now, investors believed diversification and structure could neutralize risk. Then as now, transparency lagged complexity. Of course, First Brands’ collapse won’t trigger a crisis, but it will likely (or at least should) accelerate due diligence demands, particularly on off-balance-sheet exposures. CLO investors, once focused mainly on portfolio-level performance, are rediscovering the importance of loan-level scrutiny. And so, credit selection, not just structure, will matter again.

As a conclusion, the modern credit market, which is nothing but a patchwork of bank-originated loans, CLOs, and private funds, depends on the illusion of separateness. In practice, it’s an interconnected ecosystem where the same names, the same assets, and the same risk models circulate under different labels. The real question, then, is not whether CLOs can survive isolated defaults (they can, quite easily) but whether the system built around them can withstand a world where “idiosyncratic” shocks start to spread.

In the context of First Brands, inventory-backed loans are loans secured by the company’s inventory, the auto parts sitting in warehouses or on shelves. Essentially, lenders provide cash to First Brands using its stock of goods as collateral. For example, If the company defaults, lenders have a legal claim on that inventory to recover their money. These loans were part of First Brands’ broader web of financing, alongside first-lien debt, second-lien debt, invoice factoring, and supply chain finance. They add another layer of complexity because the true value of the inventory can fluctuate, and some of these facilities were held off the company’s main balance sheet, making them less transparent to investors.