In a bid to revive Europe’s anaemic capital markets and stimulate investment, the European Commission has proposed a package of measures aimed at revitalising the EU securitisation market. This move, positioned as the first legislative initiative under the Savings and Investments Union (SIU) strategy, is presented as a means of unlocking capital for lending to households and businesses. The problem, however, is that the capital ostensibly freed up by securitisation is unlikely to make its way into the productive economy. As I’ve noted in recent weeks - albeit not always with Europe specifically in mind - there is a growing trend whereby credit provision is increasingly shifting toward non-bank financial institutions (NBFIs). This development is, in large part, a consequence of the current regulatory framework. As such, the proposed regulatory changes risk reinforcing the closed-loop dynamics of Europe’s bank-centric financial system, with minimal gains for SMEs or long-term economic resilience.

Securitisation, in theory, is straightforward: banks bundle together loans, transform them into tradeable securities, and sell them to investors. This allows banks to remove assets from their balance sheets, reduce capital requirements, and extend new credit. It also redistributes risk from the banking sector to institutional investors. In the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, however, this mechanism fell under heavy scrutiny for its role in amplifying financial instability. The EU’s 2019 securitisation framework reflected that caution, prioritising transparency, due diligence, and investor protection.

Now, amid persistent economic stagnation and geopolitical competition from the US and China, the Commission is trying to loosen those post-crisis constraints. The latest proposals aim to slash operational costs, recalibrate capital and liquidity requirements, and simplify risk assessments, particularly through adjustments to the Capital Requirements Regulation (CRR), Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR), and the forthcoming Solvency II tweaks for insurers (also mentioned in here). The rationale is clear: remove regulatory bottlenecks, reignite securitisation, and unlock fresh lending capacity.

However, this narrative breaks down when confronted with the realities of Europe’s financial structure. The first major concern is that securitisation in Europe does not typically serve its supposed primary beneficiaries, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). The logic of securitisation favours standardised, homogenous loan pools. SME loans, by contrast, are highly bespoke, difficult to aggregate, and costly to repackage. As a result, the majority of securitised assets in Europe are comprised of residential mortgages and consumer loans, forms of credit that support property and consumption rather than productive investment. In this context, freeing up capital does little to alter the real allocation of credit.

Second, there is a structural inefficiency in the market’s operation. A large share of securitised products are not even sold to outside investors. Instead, they are retained on bank balance sheets and used as collateral to access central bank liquidity, especially through the European Central Bank’s refinancing operations. This means that the supposed dispersion of credit risk - the core justification for securitisation - is often illusory. Risk remains trapped within the financial system, circulated among institutions rather than truly offloaded. In effect, securitisation becomes an exercise in regulatory arbitrage: by repackaging loans, banks can lower capital requirements without reducing underlying risk.

Moreover, this closed-loop system is exacerbated by regulatory incentives. Capital rules under Basel III - and their European equivalents - assign lower risk weights to securitised assets than to the original loans. This creates a perverse incentive: banks may shift to securitisation not to boost lending, but to improve capital ratios and optimise balance sheets. Indeed, a March 2025 report from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) highlights this dynamic. It found that while risk-based capital ratios for large global banks rose modestly in early 2024, simpler measures such as the leverage ratio and net stable funding ratio (NSFR) remained flat. This suggests that banks improved their metrics not through new equity or expanded lending, but by substituting into low-risk-weighted assets, such as central bank reserves or sovereign bonds. So, while the CRR and LCR frameworks may undergo certain amendments, the broader Basel III regulatory package will still retain several mechanisms that constrain credit creation. We can expect similar dynamics here.

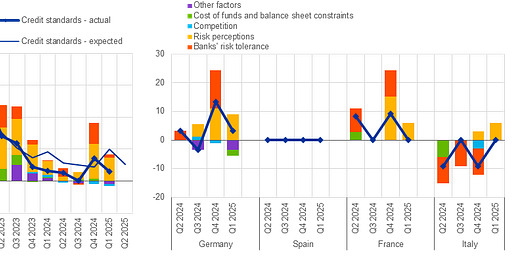

But there’s another crucial detail. For instance, take the ECB’s Bank Lending Survey from April 2025. That report confirms a decline in credit demand, not only from firms, which are facing shrinking inventories and reduced capital expenditure (reflecting both weak consumer demand and deep uncertainty over long-term projects), but also from banks, which remain deeply concerned about deteriorating firm-level conditions and an increasingly volatile macroeconomic outlook (see the figure below). Under these conditions, merely boosting securitisation is unlikely to address the structural drivers behind both the tightening of credit standards and the overall slowdown in lending.

Source: ECB

As such, the revival of securitisation is likely to follow a similar path. Rather than directing capital toward new lending for innovation, growth, or SME development, banks may use the freed-up capital to meet regulatory thresholds, fund buybacks, or reinforce shareholder payouts. Without binding requirements or incentives to lend to the real economy, the rechanneling of capital remains a vague aspiration rather than a guaranteed outcome. And while covered bonds offer a cheaper and more resilient mechanism for mortgage financing, they cannot be easily replicated for diverse SME loans, which remain structurally underserved.

This exposes a fundamental flaw in the Commission’s approach. Europe’s core financial challenge is also represented by a chronic underdevelopment of equity-based financing. European firms - especially startups and growth companies - struggle to access long-term risk capital. Fragmented capital markets, divergent insolvency regimes, and national-level legal frictions inhibit cross-border investment. As a result, promising firms frequently relocate to the US, where capital markets are deeper, investor bases broader, and exit strategies more viable.

Reviving securitisation may offer marginal benefits to bank profitability or capital efficiency, but it does nothing to resolve Europe’s over-reliance on debt-based financing. Nor does it address the systemic underinvestment in risk capital that hampers innovation and competitiveness. Worse, by encouraging complexity and allowing capital relief through financial engineering, it risks weakening resilience without any corresponding gain in productive investment.

Ultimately, securitisation cannot substitute for the hard political work of Capital Markets Union (CMU). The Commission’s plan to unveil later initiatives for equity financing is a tacit recognition of this, but it also risks being too little, too late. A truly integrated investment union would require harmonising corporate laws, strengthening supranational oversight, and confronting the national interests that block reform. Until that happens, Europe’s securitisation revival may amount to little more than balance sheet reshuffling, if you want, a technical solution to a political and structural problem.

In short, recycled loans do not equal new capital. And securitisation, while a potentially useful tool, cannot by itself deliver the investment needed to rejuvenate Europe’s real economy. Without deeper reforms, it will remain a mechanism for intra-financial circulation, not for transformation.

Glad i found your blog. Keep going 🙏